This is the last post in a series of articles focused on bullet jump research that has been conducted more than two years by Mark Gordon of Short Action Customs (Who is Mark Gordon?). In this post, I’ll provide an executive summary of what we covered and provide a few tips for how to apply this new knowledge in our load development.

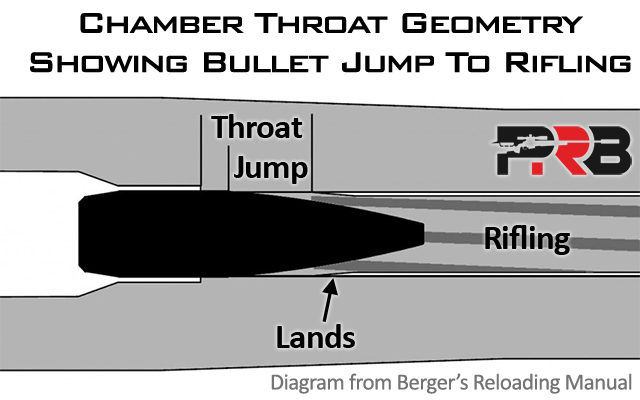

The first article provided a comprehensive overview of what 10+ of the most respected books and reloading manuals had to see about bullet jump and laid the foundation of what bullet jump is, along with other concepts like freebore, lands, seating depth, etc. Everyone from accomplished scientific researchers to world-champion shooters suggested either seating bullets into the lands or minimizing jump to within 0.020” of the lands or less for the best precision. Benchrest World Champions and other experts explained that when seating bullets close to the lands, changing bullet jump by 0.002-0.005 inches can potentially have a dramatic affect precision.

Then we looked at How Fast Does A Barrel Erode?, which focused on how quickly the lands of a rifle barrel usually erode for popular mid-sized cartridges used in precision rifle matches, like the 6mm Creedmoor, 6 Dasher, or 6.5×47 Lapua. There we saw it is common for that lands of a barrel to erode by 0.004-0.007” every 100 rounds.

That means if we’re in a major PRS/NRL match where you fire 200 rounds over two days, by the last stage our bullet jump will be 0.008-0.014” more than it was on the first stage! So, if the experts are saying that changing bullet jump by just 0.002-0.005” can have a “dramatic” impact on precision, what will 2-7 times that much do?

It seems we usually apply best practices that were established in other shooting disciplines, but if we’ll be in precision rifle matches that require 100-200 rounds, maybe our priorities should be different. In other types of competitions, like Benchrest, shooters may literally load their ammo at the range as they’re shooting. Extreme Long Range (ELR) has much lower round count. F-Class and other competitions allow sighters, so if your vertical shifted you just adjust a click or two to center your group before you fire your shots for record. However, in PRS/NRL matches first round hits matter, round counts are high, and we don’t get to fire sighters or recheck our zero.

What if instead of looking for the one exact bullet jump that provides 100% optimal precision and having to constantly adjust the seating depth as the lands of the barrel erodes, we instead looked for the bullet jump that is very forgiving AND still provided good precision over a wider range of jumps?

Now let’s think about the guys who aren’t reloading: If a shooter plans to simply shoot match-grade factory ammo, could we optimize the freebore of the chamber to be a bullet jump that would continue to provide good precision over a longer period of time as the barrel wore? I recently measured 400 rounds of various match-grade factory ammo (for an upcoming test), and it’s not uncommon for the length from the base of the case to the ogive of the bullet to vary by 0.008” or more even in within the same box of “match-grade” ammo. So, it seems like those guys using factory ammo might have similar priorities.

What if absolute peak precision might not be the only priority we are trying to balance? I totally understand that in some shooting disciplines, like Benchrest, optimal precision is the absolute highest priority and nothing else is even a close second. But what if we came at this from a different angle and tried to see if there was a way to balance priorities of both precision and a forgiving bullet jump?

That line of thinking is what led Mark Gordon to start testing bullet jump. Mark builds custom precision rifles at Short Action Customs and he brings an obsessive approach to optimizing every facet of the rifle system. His methodical and analytical approach eventually led to research on the ammo his rifles were being fed. It is important to understand Mark didn’t start this research with a theory to prove. He simply wanted to know if there were any small improvements he could make to the chambers on his rifles to improve their performance over his competition. Was there something that seemed to work well across a wide range rifles? Mark started experimenting bullet jumps and collecting data over two years ago, and some of his results seem to challenge conventional wisdom.

Mark used an approach similar to the Audette Ladder Test and OCW method, but the goal was to not find the most forgiving powder charge weight, but the most forgiving bullet jump. He wasn’t looking for the specific bullet jump that grouped the best, but the largest window of bullet jumps that provided a similar point of impact. That means the rifle would be more consistent from the start of the match to the end of it or could shoot a particular kind of match-grade factory ammo really well for a longer period of time.

Here is how Mark performed what he calls the 20-shot jump test:

- Carefully measure the bullet seating depth required for the bullet to very lightly contact the lands (i.e. 0.000” jump, but not jammed into the lands). Watch my video showing Mark Gordon’s method on how to do this.

- Load up 20 identical rounds, except vary the bullet seating depth in 0.005” increments. #1 = 0.000” jump, #2 = 0.005” jump, #3 = 0.010” jump, … , #20 = 0.095” jump.

- Fire the rounds at 600 yards, recording the point of impact coordinates for each shot with an electronic targeting system and muzzle velocities with a LabRadar.

We then analyzed the vertical dispersion of the data he collected. The goal was to find a range of bullet jumps that all had similar vertical points of impact (POI) at distance. I explained how we took the target data and turned it into the charts in detail in the Bullet Jump: Is Less Always Better? post, and I’d encourage you to go read that if you haven’t already. I won’t be repeating all that here.

The Results For Berger 105 Hybrid

Mark has repeated the same 20 shot bullet jump test using the Berger 105gr Hybrid over 10 different rifle/load configurations. That included 5 different 6mm cartridges: 6×47 Lapua, 6mm Creedmoor, 6 Dasher, and 6 BRA. Those rifles also had a variety of actions, stocks, chassis, brands of barrels, contours, and twist rates. (Read more about the rifles tested here.) While there was a lot of variation in the rifles tested, there seemed to be some similarities in terms of performance based on bullet jump.

The chart below graphs the results for all 10 rifle configurations, meaning it represents data points for 200 shots fired with the Berger 105 Hybrid bullet. The gray area is widest on the left side of the chart and it narrows as you move to the right, with the tightest area around 0.070 to 0.080” of bullet jump. That means over all 10 rifle/load configurations, the vertical extreme spreads appear to be the tightest at 0.070 to 0.080” of bullet jump.

Another interesting thing about the chart above is it appears to be saying that when you have minimal bullet jump (0.000-0.010), that is where it appears to be least forgiving in terms of changes in bullet jump. You can tell that by the widest area of gray on the left of the chart. That means if you start off with 0.000” of bullet jump, after you’ve fired 100 rounds and the throat eroded by 0.005”, and therefore you’re jumping 0.005”, you may very likely experience some vertical stringing, and in some cases it looks significant (over 1 MOA).

We also looked at what the average vertical extreme spread was over two ranges of bullet jumps:

- 0.010” wide range of bullet jumps: What you might expect the lands to erode over 150-250 rounds with popular precision rifle cartridges

- 0.020” wide range of bullet jumps: What you might expect the lands to erode over 300-500

We looked at the results for the Berger 105 Hybrid Bullets in detail (view here), but we also published research data Mark collected across 9 different rifles/load configurations using Hornady’s 6.5mm 147 gr. ELD-M bullet, and data over 6 rifles using David Tubb’s 115 gr. DTAC RBT bullet (view detailed results for those 2 bullets).

Below are summaries of the average vertical extreme spread over all 3 bullets for both a 0.010” wide window of jumps, as well as the 0.020” wide window of jumps. These two charts basically summarize all the research data presented over the last two posts, and allow you to see the trends of the bullets side-by-side. In this visual, the lower the line the better, because that indicates a smaller extreme spread.

While there are slightly different patterns between each of the bullets, it does appear none of the bullets have the most forgiving bullet jump under 0.030”. The most consistent vertical POI over a wide range of bullet jumps appears to be at 0.040” or more bullet jump. Jumps that have traditionally been considered absurdly long, like 0.080” or more, actually seem to produce less vertical shift in POI as the barrel wears than when the bullet is seated near the lands.

So What Does All This Mean?

Remember, Mark wasn’t looking for the specific bullet jump that grouped the best, but the largest window of bullet jumps that provided a similar point of impact.

This research is NOT claiming you can’t get extremely precise groups seated close to the lands or even into them. Of course, you can! However, what the data does appear to indicate is that if you are seating bullets 0.030” or less from the lands, you could experience a vertical shift in point of impact if you don’t tightly manage your seating depth and adjust it regularly (e.g. every 100-200 rounds). While minimal jump may produce smaller groups than if you were jumping 0.060” or more, that isn’t necessarily a hard and fast rule either.

Here is the question we were original hoping to answer: What if instead of looking for the one exact bullet jump that provides 100% optimal precision and having to constantly adjust the seating depth as the lands of the barrel erodes, we instead looked for the bullet jump that is very forgiving AND still provided good precision over a wider range of jumps? This research seems to make a strong case that the answer to that is found at longer bullet jumps. However, the specific “sweet spot” seems to vary based on the specific type of bullet you are using.

I created the illustration below to try to help people understand this concept. I admit this is likely grossly over-simplified, but it seems helpful. The green dots are intended to represent a group at some point in time, and the red dots are another group fired after the lands eroded 0.010” over 150-250 rounds fired.

The example above literally came from the test results for 115 DTAC. The 0.8 MOA Extreme Spread shown on the left is what was measured on average over 6 different rifles when the bullet jump was changed from 0.025” to 0.035”. The 0.3 MOA shift on the right is what the ES was for bullet jumps from 0.075” to 0.085”. Now, that does not mean the size of the groups reflects what happened, because we didn’t test group size at each specific jump.

The truth is, we could easily miss large patterns like this which occur over round counts of 100 or more. While we may fire a couple of groups in a row, we don’t do that over 100-200 rounds in a row. If you are shooting precision rifle matches where there aren’t sighters, round count is high, you can’t recheck your zero, and you’re trying to make first round hits on small targets at long range … this seems like relevant and actionable insight!

Support From A Statistician, Top-Rank Shooters & Industry Pros

As Mark began sharing this with friends in the shooting industry, he quickly met some skepticism on whether the data he collected was reliable or simply random patterns. Mark also wanted to know how much confidence he should have in the results, so he enlisted professional help in reviewing, analyzing, and processing the data. Earlier this year, a statistician named Walter Meyer analyzed all of the raw data, and he concluded that the findings showed a “strong statistical improvement in the bullets ability to hold tight vertical at distance” and “statistically significant conclusions are appropriate.” He calculated p-values less than 0.05 with two different approaches, meaning there is strong evidence that the patterns aren’t random. Walter was careful to add, “Extrapolations to other tests, bullet type and environmental conditions must be made with caution by the subject matter expert.” That means we shouldn’t assume the results for a particular bullet represent how other bullets might behave, which is an important point.

As I shared in the first post with results, after Mark started sharing his finding with a couple of the top-ranked PRS/NRL shooters, they tried this for themselves and are now believers. One of those is Scott Satterlee, who has placed in the top 10 in both the PRS and NRL in the overall national standings in recent years and is clearly one of the best shooters in the country. Over the past two years, Scott has experimented with freebore and bullet jumps all the way out to 0.250 inches! He is now on his 5th barrel since he’s been experimenting with longer bullet jumps and said, “This isn’t something that I’m still wondering if it’s true or not. After 5 barrels, I know it’s real. There is a real improvement and benefit here.”

Even more recently, a friend in the industry reached out to me after reading my articles on this research to let me know it aligned with some extremely in-depth research they’ve conducted. Scott Seigmund is Vice President of Accuracy International of North America, and here is what he shared with me:

“A few years ago, we did extensive data analysis on 338 rifle test groups involving two significantly different freebore lengths. The test involved 25 different rifles (50 in total). One group of 25 rifles had a standard CIP 338 Lapua chamber while the second group of rifles had chambers with a large increase in freebore. The data was analyzed by David O’Reilly, our operations manager and statistical expert. The results even surprised me with an increase in accuracy of 19% with the 300 grain bullets jumping about 0.100″. The test was done using the same lot of 338 Lapua 300 grain Scenar ammunition and over 2500 shots collected. While I would love to claim credit for this “discovery” it was basically gifted to us by Wade Stuteville. Wade was on to this bullet jump thing a long time ago and has done a lot of testing in this area. He’s one of the most intelligent people I know and has no ego about what he knows. Just a great, caring, and giving person.” – Scott Seigmund

Wow! The test involved 50 rifles and over 2500 shots! That sounds like some serious research, and I’d think those results are conclusive. Thank you, Scott, for your willingness to share that with the rest of us!

In further conversations, Scott said as they’ve also done considerable research on the 300 Norma Mag as they were prepared to submit their rifle for the SOCOM Advanced Sniper Rifle contract, and they found longer bullet jumps improved performance on that cartridge also.

Over the past few months, I’ve had a ton of conversations with industry pros about bullet jump, and multiple people have brought up Wade Stuteville as someone who had originally told them about the performance you can potentially get at longer jumps. Wade is a veteran shooter who was the PRS Overall Champion several years ago, and he is also one of the most respected gunsmiths in the country (read more about Wade). I’ve known Wade for several years, so after hearing his name come up so many times, I gave him a call to get his perspective.

“From what I’ve seen the big, magnum cartridges all like to have longer jumps. But, even our match cartridges (like the Creedmoors, x47 Lapuas, BR’s, Dashers) have that spot around 0.010-0.020” bullet jump where they shoot good, but usually there is another spot way back that is much wider and more forgiving. A lot of bullets don’t seem to shoot as good in that 0.020-0.050” range, but then come back into a place around 0.050+ inches where you might be able to move the jump from 0.050 to 0.100” and it shoots good everywhere.” – Wade Stuteville

Wade went on to say that when the Berger 105 Hybrid bullets first came out, he started shooting them from a 6×47 Lapua and was getting great performance seating them close to the rifling, and he’d consistently keep them tuned with very minimal jump. After a match he’d clean his gun, remeasure the distance to the lands, and then take any ammo he had left over from the match and bump his bullet out to the new seating depth to keep them close to the rifling. Wade went on to say that he first discovered the longer bullet jumps on accident. He had two 6×47 rifles that were basically identical except one had more rounds on it than the other. One day he shot the ammo that had been tuned for the chamber with less rounds on it in the other rifle, which meant it was jumping much longer – and it performed as well as anything he had shot! Wade said that is what triggered him starting to experiment with jump. He discovered on his 6×47 rifles he could start off jumping the 105 Hybrid’s around 0.080” and never have to change the seating depth over the entire life of the barrel and it’d perform great the whole time. Wade explained, “Over the life of the barrel, my jump might change from 0.080” to 0.130” or something, but it never really comes out of tune. And I’ve had a lot of cartridges that have been that way in the past.”

While much of this seems to be counter to “conventional wisdom” (which I outlined in the first post), there sure seems to be some pretty compelling evidence from this research and the experience of other respected sources in the industry.

Load Development Tips

I originally planned to make a recommendation for how to integrate bullet jump into your load development. However, I’m still experimenting with the best way to do that myself. So instead of prescribing how to go about it I will simply offer a few tips based on this research data and share suggestions from others in the industry. Armed with that information, you can make an informed decision on how you might try this out for yourself in your load development. Also, if you have a good way you test jump during load development, please share that with the rest of us in the comments!

Important: Adjusting seating depth to match your rifle’s throat/freebore and maximize accuracy “is fine, but bear in mind that deeper seating reduces the capacity of the case, which in turn raises pressures. Going the other way, seating a bullet out to the point that it actually jams into the rifling will also raise pressures.” – Sierra Reloading Manual

Measure Your Distance to The Lands With A Precise Method

Until a few months ago, I was measuring the distance to the lands like most people do. I thought it was accurate, but I was off by almost 0.100” in some cases! No joke. It turns out you can seat a bullet well into the lands without it leaving marks on the bullet or getting stuck in the rifling. Measuring the distance to the lands in a way that is accurate and repeatable is harder than it seems. There are only two methods I know of that allow you to measure the distance in a way that is repeatable within +/- 0.002”; Mark Gordon came up with one and Alex Wheeler teaches another. You can learn more about both on this page: How To Measure The Distance To The Lands On Your Rifle Barrel.

If you take just one piece of advice from all this, I might suggest it be to try this measurement method. I bet the results surprise you. Honestly, if you are not measuring the distance to the lands with one of these methods, I bet you aren’t testing what you think you are.

Measuring CBTO vs COAL

If you are concerned with bullet jump, you need to measure from the base of the cartridge to the bearing surface of the bullet (i.e. CBTO or Cartridge Base To Ogive), not from the base to the tip of the bullet (i.e. COAL or Cartridge Overall Length). Even if bullet tips were completely uniform (and they never are), remember that bullet jump is the distance a bullet travels before it’s bearing surface touches the rifling in the barrel – so measuring CBTO (Cartridge Base To Ogive) is a much better way to ensure that jump is uniform. (Read more: Article from Bryan Litz on CBTO vs. COAL)

To measure this, you need a caliber-specific bullet comparator. I use one from Hornady, and you can get it in a kit with 14 caliber inserts that covers all major calibers on Amazon.

Establish Seating Depth, Then Powder Charge

Mark tested 3 different loads for the 6.5mm Hornady 147 gr. ELD-M from the same rifle, and all of them resulted in a very similar “sweet spot.” Regardless of the shooter, order the shots were fired in, or amount of powder used, the data showed a sweet spot around 0.060” of bullet jump each time the test was run (read more here).

Alex Wheeler, owner of Wheeler Accuracy and a respected gunsmith who has built some of the best shooting 1000 yard Benchrest and F-Class rifles, seems to agree with this idea:

“From my experience powder charge will not drastically affect the correct seating depth. Meaning if you change your powder charge the gun will not go from preferring a .010 jump to a .060 jump. It may move a few thousandths, but I think you can use any powder charge you want to rough in on seating depth.” – Alex Wheeler

After doing more than 2 years of research on bullet jump, Mark Gordon believes bullet jump is a more course adjustment to a load than powder charge, meaning a small tweak to bullet jump can often has a larger impact on performance than a small tweak to powder weight. I remember where I was when I first heard Mark propose that, because it was so foreign to my way of thinking. I’d been approaching it from the other direction completely. However, I can’t say that doesn’t fit my experience, and if that is the case then it makes sense to start with the most course adjustment before we move to further steps to refine a load.

Scott Satterlee explains that when he does load development, he starts with the same powder charge weight that worked best in his last barrel or if he’s working up a load from scratch he’ll simply start with a powder charge he knows is safe. Then here is his two-step load development process.

- Bullet Jump for Group Size/Shape: Scott tests various bullet jumps to find the one that produces the smallest vertical extreme spread at long range. He prefers to tune a load at either 800 or 1000 yards. In this step, he is 100% focused on group size and shape. He is not just looking for a small group, but the shape is important too. Scott believes a group in the shape of a triangle is great, and one that looks like the 5 on dice is outstanding. He does not like to see a group that is short and wide, even if the spread is tiny. Scott said from his experiencing, following a group like that leads to the road of destruction, because it is deceptive and won’t be a consistent performer long-term like a group in those other shapes. Scott explains that what you’re looking for is not just a small group, but an even distribution in the shots within the group. From a statistical perspective, I think Scott is saying that you want a very small Average Distance To Center (ATC), which is also sometimes called mean radius. That doesn’t mean you can ignore the extreme spread, but he doesn’t simply pick the group with the smallest extreme spread. (I’ll touch more on the specific jumps Scott tests in the next section below.)

- Powder Charge for Lowest Velocity Extreme Spread: Once Scott has found the optimal bullet jump, he starts varying the powder charge with the goal of finding the lowest extreme spread (ES) in muzzle velocity. In this step, Scott isn’t looking at group size and even said he might just fire the bullets into a berm, because he is 100% focused on finding consistent muzzle velocities. While many shooters reference the muzzle velocity standard deviation (SD), Scott prefers to use ES as his guiding metric. He says occasionally you’ll have one shot out of a long string be very different, and SD glosses over that anomaly more than ES does, but that kind of thing could result in a miss in a match.

For more details on Scott’s approach to load development, I HIGHLY recommend listening to a recent podcast where he shares all the details. It is VERY interesting! Modern Day Sniper Podcast: Scott Satterlee & Handloading. The podcast is hosted by Phil Velayo and Caylen Wojcik, who are top-ranked precision rifle shooters and they know what they’re talking about. At SHOT Show earlier this year, Scott Satterlee, Mark Gordon and I had a long conversation, and this podcast is very similar to listening in on our conversation at SHOT. Scott has an unorthodox/pragmatic approach to load development, which I won’t attempt to repeat here. I promise it will challenge how you think about this stuff and I bet you walk away with at least one or two good ideas for how you could improve your own approach.

What Jumps to Test

Let’s first look at the data from Mark’s bullet jump research. Below is a little different view into the same data we’ve looked at over the last two posts, which helps visualize where the “sweet spots” are for the three bullets Mark has compiled considerable data for:

You can see all of the bullet jumps that produced consistent vertical POI at long range were at least 0.040” from the lands or more. Most of the time it was actually 0.050″, which is also what Wade Stuteville said his experience was. Remember, this isn’t saying you can’t get tiny groups at shorter bullet jumps, but the data is simply showing that shorter jumps are less tolerant of changes in bullet jump. At least for these three bullets, jumps under about 0.040-0.050” are not as forgiving and consistent as the distance to the lands changes.

So if finding a forgiving bullet jump is a priority for you, the data seems to be suggesting you start testing around 0.040” and go out from there. While Mark’s testing was limited to bullet jumps out to 0.095”, Scott Satterlee has experimented with bullet jumps out to 0.250” on his 6mm Creedmoor – and Wade Stuteville said he’d also tested cartridges out 1/4 of an inch and even some closer to 3/8 of an inch (0.375″)! However, while this may change slightly barrel to barrel, most recently Scott has been jumping around 0.120”.

While you might find good precision beyond 0.120”, longer jumps may require additional chamber freebore, meaning a gunsmith needs to modify your chamber to be able to jump that far. With traditional chambers, jumping 0.120” or more may require you to seat the bullet too far in the case. Scott says that he never wants the bearing surface of the bullet to be below the neck/shoulder junction on the case. That helps you stay away from the base of the neck where the “dreaded donut” could lead to shot-to-shot inconsistencies (more on the donut). Also, seating bullets further out allows more volume in the case which can actually allow you to achieve faster muzzle velocities without increasing pressure. (Read Bryan Litz explaining more about this.)

Scott Satterlee says when he is testing jump, he doesn’t do anything too drastically different than what the Berger Bullets Reloading Manual recommends (read that here), except he usually tests with jumps at 0.030”, 0.050”, 0.080”, 0.100” and 0.120”, rather than the intervals Berger suggests. Scott said sometimes he may just start at 0.050″. After he figured out which one groups best (as explained in the prior section), he then tests jumps a little below that and maybe 0.010-0.020” above it to make sure it continues to group well. That is how he makes sure that is a “durable” jump.

By the way, I do want to point out that Berger Bullets is the only reloading manual or published book I’ve found that actually recommends testing bullet jumps out to 0.100” off the lands or more. As we saw in the first article in this series, virtually everyone recommends jumping 0.020” or less for the best precision. Berger is the one outlier I’ve come across, but this research seems to confirm that they have been giving us good advice. Thanks, Berger!

I’ll try to side-step the debate of how many rounds you need to fire at each bullet jump for your results to be “conclusive” from a statistical perspective. There has been a lot of debate on that topic in the comments of this series of posts. There seems to be a purist/mathematical view which leads to very large sample sizes, and a practical/pragmatic view that says you can do it with one 5 shot group. I’ll leave it up to you guys to decide where you fall. Simply put, the larger the sample size the more confidence you can have in the results.

Alternatively, you could do load development in a similar fashion to Mark’s 20-shot jump test, testing from touching the lands out to 0.095” or even 0.120”. However, the statistician Mark had analyze the data did say that testing in 0.005” increments didn’t seem necessary from a statistical perspective, although having data in 0.005” increments helped as he did calculations for p-tests to ensure these results were statistically significant. His professional opinion was that tests in 0.010” increments would have reached the same conclusions.

If you do want to use something more like Mark’s 20-shot jump test, you might consider running through it at least 3 times to confirm the patterns you are seeing persist. To conserve barrel life, you might consider starting at 0.040” or 0.050″ from the lands and test in 0.010” increments, as the statistician suggested. If you did those things you could test the following 9 jumps with 3 to 5 shots each, and then graph the vertical POI of your results and look for the flat spots: 0.040, 0.050, 0.060, 0.070, 0.080, 0.090, 0.100, 0.110, 0.120. For more details on Mark’s approach and what I mean by “flat spots,” read this post.

Adjust Your Parallax!

My last tip is when we’re doing these kinds of tests and making decisions based on relatively minor differences in group size or patterns in shot-to-shot POI, it is especially critical to ensure your parallax is adjusted properly. Even at 100 yards, you can have shot-to-shot variance from parallax, which just adds noise to your data and can result in false positives and bad decisions. Not sure how to adjust your parallax? Watch this video

Shortcuts To Loads & Components

While some people love to tinker with load development, there are others that simply want to find a load in the shortest number of steps possible. For the latter group, I want to mention a couple of resources that could be potential shortcuts for finding a good powder charge or combination of components to use.

- What The Pros Use: Load Data. This series of articles shows what components and specific powder weights the top-ranked precision rifle competitors in the country are running in their match ammo.

- My Complete Load Data: This is the page I use to keep track of all my load data, for cartridges like 6mm Creedmoor, 6XC, 6.5 Creedmoor, 7mm Rem Mag, 300 Norma Mag, 338 Lapua Mag, 375 CheyTac, and more. It is actually what I use to reference my own load data, so it’s always kept up-to-date.

The Point of Diminishing Returns: How Much Does It Matter?

Finally, there are a couple timely reminders we should keep in mind. If you enjoy tinkering, then I don’t want to pour cold water on you. But there is definitely a point of diminishing returns when it comes to load development. For example, reducing your group size from 0.5 MOA to 0.1 MOA may only increase your hit probability at long range by 1-2%. That isn’t just my opinion, but is based on hard data you can see on the chart below and read more about here: How Much Does Group Size Matter?

Shrinking your muzzle velocity’s standard deviation from 10 fps to 3 fps may only increase your hit probability at long range by 1-2%. You can see that in the chart below and read more about that here: How Much Does SD Matter?

As always, it depends on the size of the target and other factors. However, if you aren’t shooting extremely tiny targets or Extreme Long Range (ELR), and you aren’t competing at the absolute highest levels (i.e. you aren’t one of the top 25 shooters in the country) – tuning your load to the Nth degree may not matter as much as you think. Hopefully, those stats help us put into context that point of diminishing returns.

I wrote an entire series of articles called “How Much Does It Matter?” that took an objective approach to those factors, as well as many others. If you have not ever read that, I would highly recommend it! I promise you’ll learn something, and probably find a few surprises. I know I did!

Series Wrap-Up!

I hope you guys enjoyed this series of articles on bullet jump as much as I did! I know it challenged a lot of things I had simply been assuming were the unquestionable truth in the past. Even if you’re a still a skeptic, I’d challenge you to go try it for themselves. That is exactly what I plan to do!

And to Mark Gordon – Thank you for being willing to share your hard work with the rest of us! I know you could have kept all this data private and thought of it as a competitive advantage for Short Action Customs, but we appreciate your openness. We all got to learn something from it, and this is a huge contribution to the shooting community! It also clearly shows the methodical approach and extreme lengths you go to at SAC to ensure the rifles and products you make are performing at the highest levels. Lots of people think about doing stuff like this, but very, very few execute on that and see it all the way through. Thank you for your passion and extreme internal drive for excellence!

I’ll end with this quote, which seems fitting for this topic and Mark’s research:

“It is easy to sit about the fireside or under the shade of the home trees, after a day’s work at competitive rifle practice, and talk over the causes of bad shots, and it’s good fellowship’s pleasures are not to be denied; but it’s not so easy to prove by repeated and, maybe, costly experiments that our fine theories are correct”. – Franklin Mann, The Bullet’s Flight From Powder To Target (Published 1909)

Here are links to all the articles in this series:

- Bullet Jump & Seating Depth: Best Practices & Conventional Wisdom

- How Fast Does A Barrel Erode?

- Bullet Jump: Is Less Always Better?

- More Bullet Jump Research!

- Mark’s 18-Shot Bullet Jump Challenge!

- Bullet Jump Research: Executive Summary & Load Development Tips

| Find this interesting? | ||

| Subscribe Be the first to know when the next article is published. Sign-up to get an email about new posts. |

or … |

Share On Facebook |

PrecisionRifleBlog.com A DATA-DRIVEN Approach to Precision Rifles, Optics & Gear

PrecisionRifleBlog.com A DATA-DRIVEN Approach to Precision Rifles, Optics & Gear

what a fantastic series and we await those in the future

Thank you

Fred L Walls

Thanks, Fred! It was fun for me to learn about this and share it as well! Glad you enjoyed it.

Thanks,

Cal

Thank you for this series! I have learned allot and I hope to improve my hit percentage at 1 mile!

You bet, Jay! I appreciate you letting me know you found it helpful.

This is such a fun game, and it’s amazing how much we’re learning over the past few years. Hit probability at 1 mile today compared to 10 years ago is astronomically different. No better time in history to be a long range shooter! 😉

Thanks,

Cal

Cal, I’ve read with interest your thoughts on employing greater jumps for consistent accuracy over barrel life. I have a RPR in 6.5 Creed that when new I had to use a jump of .085 using Hornady 143 Gr ELD-X bullets. This jump was to allow proper magazine function. The gun when new was a .5 MOA shooter and sometimes much better. Now after 550 rounds these same loads are jumping .135 and the accuracy is holding. So two things I take from your posts–1. this barrel eroded at .0055 per 100 rounds fired and 2. it was a good shooter at .085 jump and now at .135 jump it is still performing well.

Before reading your posts, I was not as aware of the barrel eroding issue as I should have been and now don’t fret if magazine restrictions forces me to have greater bullet jumps. Thanks for all the great research.

Thanks, Keith. That is very interesting. Before this, I was like you and really hated when I was forced to seat short to stay in mag length and couldn’t get closer to the lands. I’m not sure why I didn’t question whether that was really necessary or not, but I guess I just never did. But this has really opened my eyes as well.

Your results sound very similar to what Wade Stuteville said his experience was. I actually gathered all that on a phone call with him earlier today, and I remember him saying he’d found that you could usually find a spot around 0.080″ and the barrel might eventually erode to where his ammo would be jumping closer to 0.130″, but it would keep shooting great the whole time. You are using a different cartridge and bullet, but that is still within just 5 thou of what you just said! Ha!

And thanks for sharing what you’ve measured your erosion to be on your 6.5 Creedmoor. I am actually doing some other research on 6.5 Creedmoor’s right now that I plan to start publishing in a month or two, and I’ve been firing hundreds of rounds through one myself. I haven’t measured how much the barrel has eroded yet, but I expect it to be very similar to what you measured.

Thanks,

Cal

Great series! I’ve been waiting for this section since the last!

Question for you.

Can seating depth and ocw development be done on new brass? Or should I wait till it’s once fired so it can be resized? Maybe only seating depth can be done on new brass?

Thanks for any pointers.

Andrew, I’m not sure, but my gut would be similar to what your’s sounds to be. I would think you could test for jump length with new brass, but fine tuning for powder charge might be better if you had once-fired brass. At the very least, I’d run the new brass through a neck expander mandrel to ensure all the neck tension was the same. I’ve been using the ones from K&M lately, and they seem pretty ideal. I would bet you could get most the way there on your load development with new brass, but you might just confirm what you find for jump and powder charge once you resize the brass the first time.

Thanks,

Cal

Thank you Cal!

Any way you could ask someone that knows what they are doing what they do with new brass? I honestly cant find the answer. I’m new to reloading rifle rounds and I want to not make any big mistakes!

Sure. I know there are literally hundreds of guys reading these comments that are world-class shooters. I also know Mark Gordon is reading these, and I bet he has some opinions.

Can one of you guys offer any advice on load development using brand new brass? Does Andrew need to wait until he has once-fired brass to do bullet jump tests or OCW tests?

Thanks,

Cal

Hi Cal,

Thanks for asking the question. I hope some one responds! If not please let me know if you ever talk to one of them. I’m trying to hold off loading till I know for sure to not waste components.

Thank you,

Andrew

Cal, you might want to read this, I been reloading 40 years out of my 73 on this planet and what’s in this article by a young guy Bryan Litz is on the money, the more jump the less cartridge capacity.

https://bergerbullets.com/effects-of-cartridge-over-all-length-coal-and-cartridge-base-to-ogive-cbto-part-1/?fbclid=IwAR1RZAgbZu6qjQonQws17xVz4coGS73x3x3IbK3ooBAzgq-YykNqvPZrHv8

Totally, Frank! I’ve actually read that article a few times, and even think I linked to it somewhere in this post. It is a great article. Bryan is a sharp guy and does a great job explaining things in a practical way. Great article! Part 2 is worth reading as well.

Thanks,

Cal

We who have shot bench and F/class been running at lands for years and years, I believe the young guys are trying to reinvent the wheel, I couldn’t find par two of Litz article was it right in front of me, sometimes when I’m on my laptop I put my glasses on top of my head, then I’m running around the house looking for them, like now.

Yeah, but Benchrest and F-Class have different constraints and goals. The winners there prioritize different aspects than what are relevant in PRS & NRL style matches, so it only makes sense that maybe we’ll have different approaches at times.

Thanks,

Cal

Accuracy is accuracy, the object of each is to hit your target, in one you are shooting at 1/2 moa target at all ranges and in PRS your shooting at 3 and 4 moa targets from many position, accuracy and FPS work just as well in both disciplines, why be under powered plus you may not be getting the full potential from you rifle/cartridge, it’s like horse power you can’t have enough. more FPS helps Wind and drop.

Always nice chatting with you.

Frank

First, I have to say that I’ve shot in a ton of PRS/NRL style matches, and I can’t remember ever once seeing a 4 MOA target! The majority are 1.5-2.0 MOA and yes we hit those from many improvised positions. There are also a few targets that are smaller (probably the smallest I’ve seen is 0.8 MOA, and anything 1 MOA or smaller is shot prone) and a few larger (maybe up to 3 MOA for standing, unsupported shots or very, very long shots that are stretching the capability of the rifle systems being used in the match).

I do agree that precision is important to any rifle game, but it isn’t the only priority. The fact is, we have high round counts (up to 200 rounds fired over 2 days) and you can’t recheck your zero and first round hits really matter. Sometimes you don’t even engage the same target twice, so your dope has to be on. If you aren’t getting first round hits, you won’t finish in the top half, much less the top 20. If your POI is shifting around, which this research data clearly says it does enough to cause misses, then that is as important as having tiny groups in this game. Hits are the goal, so it is about trying to minimize whatever factor is most contributing to your misses. It might not be groups size! It’s actually ridiculous to think that any application with a long range rifle must have the same priorities. A long range hunter (or a sniper in Afghanistan) needs precision, but also needs to prioritize things like the amount of energy the bullet is carrying along with the terminal performance of the bullet. A PRS guy doesn’t just need to think about precision and group size, but also consistent muzzle velocity, a bullet that minimizes wind drift, being able to stay on target to spot your own impacts, the rifle being able to function without interruption in dirty field conditions, the bullet hitting the target with enough energy for the RO to call the impact, your point of aim and point of impact staying aligned through 200+ rounds, and other things.

There are trade-offs at every corner, so blindly pursuing the tightest possible groups at any cost may not be the way to maximize your score in this game. In fact, I’d contend it isn’t. It also sounds like a PRS Champion agrees. Sure, we all like to shoot tiny groups … but honestly I have a stronger desire to hit more targets and finish higher on the leader board than to punch tiny holes in paper. So while we all like more horsepower, at some point if it isn’t the thing that is keeping you from winning the race … spending time focusing on adding more is not doing anything for you.

Sorry for the rant! Nothing against you, Frank. I just know there are probably a lot of guys out there that might have a similar perspective, and I just think it’s very shortsighted and it’s what leads to us blindly adopting practices from different disciplines without exploring or at least questioning whether they are the best thing for our application. That can hold us back, and even make guys who do try something different feel stupid. I hate it when people feel stupid … and I don’t think it’s stupid to entertain ideas like this.

Thanks,

Cal

Hi Cal,

Good read, and certainly counter to everything I’ve assumed as truth for decades.

Louis

PS – Like you, I’m a degreed MSME, but I am retired so much of my brain has gone soft.

Thanks, Louis! It really challenged my view as well. I actually “short-throated” two barrels that I had chambered just a few months ago, because I wanted to be able to reach the lands with the 110 gr A-Tip’s I’m using now and continue to seat those bullets out as the barrel eroded. So clearly this is a new concept to me! Wish I could go back and undo that! Oh well, I shoot barrels out pretty frequently, so there is always another opportunity to go back to SAAMI spec chambers next time, or maybe even trying longer freebore. I say all that to just show that we’re all always learning!

Thanks,

Cal

Hey Cal, thanks for another great series of articles.

In all your conversations and data analysis about bullet jump, have you acquired any insight regarding bullet jumps for monolithic projectiles? Many of us are now forced to hunt with all copper bullets and I personally have struggled to get precision close to lead core bullets. I know this is a deep rabbit hole, but any information you can share on the subject would be greatly appreciated.

Thank you,

Joe

Hey, Joseph. I know Stephen Hurt from outeredgeprojectiles.com.au makes copper bullets, and he’s chimed in on this series to echo that a lot of this matches their research on solids as well. I went back and looked at his comments for tips and he said “Copper bullets usually like a jump of 0.9 – 1.3 mm or 35 – 55 thou (I say usually – there will always be an exception pop up somewhere!) for best performance. This of course dependent on the alloys and coatings used.” In another comment he said “Regarding the larger calibres, (and by larger – I mean 375 CT and up) we use a jump of 0.065″ for best results (with our bullets), as opposed to the 0.050″ we recommend for the smaller calibres and cartridges.”

Barnes Bullest also has some info on their website, which recommends longer jumps for their solid bullets as well:

Hope that helps!

Cal

A great series of articles, thanks for sharing , i am you BIG fan .

looking forward to your more research and testing about precision rifle shooting

have a nice day

Thanks!

This is pure knowledge – best precision, LR. source of information. Thanky you for such great series of articles.

Thanks! I’m certainly trying to put out high quality information, so it means a lot to hear someone say that.

Thanks,

Cal

Very interesting and useful report on bullet jump. I want to point out that Barnes also recommends a longer jump, on the order of 0.05″ or greater. This has been interpreted by many as being an idiosyncrasy of solid copper bullets, but maybe it’s not. Also, it’s interesting to note that Tikka chambers are notoriously long, with mag length limitations sometimes requiring very long jumps with these rifles that are renowned for accuracy. May be the Finns and the solid shooters were on to the same thing a long time ago.

Thanks, Mike. Glad you found this useful. You’re right. Barnes does recommend “longer” jumps in this same range. And there are a few manufacturers that use longer throats. Scott Satterlee talks some about that in the podcast I recommended in the post. He believes that is one of the ways experienced manufacturers can make rifles shoot so well at such a low hard cost of components. I’d highly recommend checking out that podcast.

I do think some people have been onto this approach for a while, and the shooting community (including me) was simply close-minded to it … and even criticized people for it, without really putting it to the test themselves. That’s why I was so excited when I started getting into this research. It really takes an objective, scientific approach and as a result our understanding is challenged and deepened.

Thanks,

Cal

Hi Cal, Great series !

It looks like Sako were on to this “long jump” thing decades ago. All 6 of mine, L-series and A-series Finnbear, Forester and Vixen sporters from the 1970s and ’80s have a freebore of several millimetres. I worried about .015″ jump at first, then just fiddled about till I found a sweet spot for the seating depth. OK, they don’t shoot groups that will win benchrest competitions, but all can shoot 3/4 MOA to 1/2 MOA depending what I feed them (and how steady I hold them !). I’ve recently bought 2 Tikka T3 Varminters that also have longish throats. Going .015″ shorter on the 22-250 seating depth a year ago halved my 100 metre groups.

Looking forward to the next PRB post !

Thanks, Anthony. I do think you’re right. There are a few manufacturers who have been on to this for a long time. If you are going to mass-produce something and still want it to perform well … this looks like the ticket.

Thanks,

Cal

Hi Cal – thank you and Mark’s excellent testing and observations.

I would think the point of impact shift would have to due to two main components: changing barrel harmonics and bullet engraving. A chamber built to the specific brass and bullet reduces the bullet engraving issue. With no other change we have moved group sizes by a full moa while testing our barrels working with chamber details. The root reason why many guns shoot fired brass better than factory first rounds.

As you know we are after the harmonics of the barrel. We identify at least three components of the harmonics and the recoil event. One primary events is the engagement of the lands by the bullet or rather timing. You are pile driving an oversize pin into a small hole with an instant 55k hammer blow so to speak. To date we have only adjusted bullet seating depth to help control hot loads. Our .338 and under starts at .025″ and moves out and the above .338 start at .050″ and move out. Part of the reason is to control recoil/bolt set back when we load and test at 70deg in the midwest and travel to a 100deg temp down south or west. With full admission I recognize the expertise brought to the table here which far outweighs my own but I do like trend lines that start at different points of view/aspects. While we have tested extreme powder charge ranges and bullet weights and their impact on our group and group location I will be interested in the impact of changes in seating depth. In fact I think we will start tomorrow with a 33xc and 1000yds. Are there any data/charts that show overall group size at extended distances? Velocities variations? Recoil event?

Hey, John. Thanks for chiming in. For those who don’t know, John is an inventor of a few cool technologies including the Charlie TARAC and structured barrels. John is one of the true innovators in the industry, and not someone who is copying or simply trying to make incremental improvements over what everyone else is doing. I say that because I have a lot of respect for John’s thoughts here and I would recommend everyone reading this pay attention too.

Your reasoning on what is changing POI shift sounds plausible to me, but ultimately I’m not sure what the root cause is … only that there seems to be a measurable outcome here. I don’t think we have any theories on why this happens, but your’s sound good! 😉

I have heard your structured barrels don’t seem to need to be “tuned” to a specific load. In fact, I remember one guy reviewing one of your structured barrels was doing standard load development on it and said he uncovered that no matter what bullet or load he used they all seemed to go in the same spot. I do think you’re right about a lot of this having to do with barrel vibration/harmonics. If you can reduce that significantly, it seems like you’d reduce the need to tune significantly. However, some of this may have to do with internal ballistics and how pressures build or gas blow-by happens, and not just how the barrel moves. I’m not saying it does, I’m just saying it’s plausible that there are lots of things at play here and even lots of factors that are interdependent and have complex interactions that we may not fully understand. I just don’t know. But I bet what you’ve suggested accounts for a large portion of the why behind this.

Mark didn’t really test group size at different jumps, but just the relative POI shift from one jump to another. So we don’t have that data. He does have some muzzle velocity data, and I chose not to focus on that, because it didn’t seem to directly correlate to the POI shift. Don’t get me wrong, they were related, but it doesn’t fully account for the shift you saw at long range, so I chose instead to focus on the actual impacts at long range. Some of that was simply to not overly complicate all this. It was already very technical, and I was trying to keep it approachable by non-technical readers too. I’m not sure if I’ve noticed any differences in recoil at different jumps, but I haven’t personally hooked up any high-speed sensors. That is an interesting question. I do think it affects chamber pressures, so in theory it could … but if the muzzle velocity is not drastically different I would think the recoil event would not be either … but that could be grossly over-simplifying what is going on here.

All great questions! I would be very interested to know what you find with the 33xc. I think on a magnum like that, you should test out to at least 0.120″, if not 0.150″ … if you’re able to without getting too deep in the case. I would expect the findings might be similar to the Accuracy International research I referenced in this post, which found an improvement around 0.100″ of bullet jump. But that is just a guess! Who knows! Like everything, it’d be better to go test it and see than to theorize about it on the internet! 😉

Thanks again for sharing your thoughts, John. I always like hearing what you’re thinking!

Thanks,

Cal

Thank you Cal- you have your own special folder on my computer for a reason. I thought it was a gold mine when I found you a few years back.

The 33xc will be tested to at least -.100 depending on powder compression. More if we can seat the bullet to the correct target. I want to change as few variables as possible and obtain some base lines. We will shoot both 300Berger and 285Hornady at 3150 and 3300 +/- respectively base lines.

I do agree separate events, though overlapping. I would believe the forgiveness of the powder charge goes up as the unit area/throat goes up. A simple calculation is impact G-Force: it is amazing how fast G-Force values drop with the addition of minimal deceleration pad/distance over a solid. We learned that dropping a bunch of rifles on concrete. The unit area of a throat has to act the same.

If we can increase the range of value the bullet sees and its direct impact on the rifling, life becomes more predictable. Top Fuel dragster and a Z06 Corvette- consistency with minimal fuss. As that prediction value goes up the ability to model the chamber value goes up, for us the harmonic vibration becomes predictable.

I love car analogies, a bullet pushed into a land has some x-value it must overcome to start moving. If you torque a bolt you cannot go part way and then continue. If you miss your value you have to start over/loosen the bolt due to the friction/interaction of the surfaces. During that initial action the pressure is going to z?… Small changes rapidly alter the initial x-value.

Recoil: all of us have experienced the “hot load”, hard lifting bolt. Many times the moment you pull the trigger you notice the recoil impulse- rather the difference- like a sharp hammer hit. It will be an interesting value to initially note during testing vs velocity.

Part of our design goal specifically looks at the throat and steps to mitigate the initial “shock wave” of the bullet engaging the rifling.

I will let you know what the initial results are… now if I can only shoot well and not make a fool of myself.. the jerk on the trigger.

Cal may I suggest a method to increase randomization in the data collection, perhaps including double blind collection from the shooter. may be too painful (numbered and randomized rounds to specific targets that are in close proximity) but it may improve the data for many people. Been bit by lack of randomization before! Very nice series and blog. thanks much.

Paul in Oregon

Hey, Paul. This was really Mark’s research that I just analyzed and presented. While I love a good randomized, double-blind experiment, in this case I think that may have introduced so much complexity that I’d be concerned it might introduce considerable error into the collection. Of course there is some way to manage that, but like you said … it might add a lot of pain!

Thanks,

Cal

Great stuff! Thanks, most of us don’t have the resources to do those kinds of tests so it’s saving the shooting community a lot of money.

My question is about barrel life. I think it was Scott Satterlee who mentioned extended barrel life as seating near the lands for accuracy was no longer the main factor. So what should one expect for barrel life and how do you now determine when the barrel is “toast”.

Hey, Marc. I’m not sure this would extend accurate barrel life. I’m at least a bit skeptical that it’d have a significant impact. It sounds like what Scott was saying was that being able to reach the lands with the bullet would no longer be a constraint and so it wouldn’t be for that reason you’d call a barrel toast. I still think the barrel might get to the point where the muzzle velocity becomes inconsistent or less predictable and/or groups eventually open up. I don’t have the experience shooting out barrels at longer jumps that Scott does, so I’m not sure … but there is still a lot of heat and pressure in that chamber, so it just seems like it’d wear out a barrel in about the same amount of time.

Thanks,

Cal

Hi Cal

You put together a great series! Thank you. I intend to try out some of the suggestions as soon as our local ranges reopen.

In the mean time I am wondering if you or any readers have some thoughts on some very rapid barrel erosion in a RPR in 6.5 Creedmoor.

I worked up loads using 40.1 grains of H4350 and a 140 gr. Hornady ELD-M bullet.

I have fired only 451 rounds through the rifle. Over the last 339 rounds the CBTO went from 2.105 to 2.211. This is an increase of .0312 in. per 100 rounds. This appears to be about 10X the increases others are experiencing. Accuracy has gone from approximately 1/3 MOA. to just over 1 MOA .The Ruger factory said to try some Hornady factory loads to see if it is just “normal wear”.

With this kind of erosion, I will need a very forgiving jump!

Any thoughts on what’s going on?

Thanks, John. That is surprising about the level of barrel erosion you’ve seen in your Ruger Precision Rifle. I guess my first question, is how were you measuring that? Did you use the Mark Gordon method or the Alex Wheeler method?

I actually bought a Ruger Precision Rifle recently for another test I’m currently working on behind the scenes. I have fired almost 300 rounds out of it over the past couple of weeks (95% of that was match-grade factory ammo), and I did remove the barrel and carefully measure the distance to the lands before the first round fired, just so that I’d have good data on the 6.5 CM erosion after I fired all the ammo I had planned. I still need to shoot a few more rounds out of it for my test, and then I’ll remove it and measure the distance to the lands again. I am expecting somewhere in the 0.005-0.007″ per 100 rounds … so your 0.031″ scares me a little. But, I’ll try to remember to come back and let you know what I find in a couple weeks once I finish my test and remove the barrel to measure.

If anyone else has any experience or wisdom here, please chime in.

Thanks,

Cal

“like the 6mm Creedmoor, 6 Dasher, or 6.5×47 Lapua. There we saw it is common for that lands of a barrel to erode by 0.004-0.007” every 100 rounds.”

This is NOT been my experience. Not even close. In latest 6 Dasher barrel .005″ movement from round count 100 to 500 rounds. If you are saying .005″ in 100 that would be .035″ in 700 rounds. I am highly skeptical of that. Certainly there could be more with 6mm Creedmoor, however. but .007″ in 100. Again, that doesn’t seem right at all.

Perhaps cleaning method makes a difference. I use WipeOut, minimal brushing. Avoid abrasives.

Paul, I am confident in the 6mm Creedmoor and 6XC numbers. Those were ones I’ve measured myself. The other numbers came from other people, but they seemed like knowledgeable and detailed guys – I just can’t confirm how hard those numbers are. You should go read that post and it explains in detail what I mean by those numbers: https://precisionrifleblog.com/2020/03/24/how-fast-does-a-barrel-wear/

I also don’t use brushes the majority of the time, and if ever do it’s a nylon brush. I use Bore Tech Eliminator, so it’s not an abrasive and doesn’t have ammonia. Most of the time I just allow time for the solvent to work, and run patches until it’s clean. I’ll run a few patches to get the bore soaked, then start a 15 min timer and walk away … then go run a few patches and get it soaked again … and repeat until clean. In fact, I actually don’t always clean to squeaky clean anymore – unless I’m testing or doing some kind of calibration. I’ve talked to enough barrel manufacturers to know that people often do more harm to their barrel with excessive cleaning than they do good.

I don’t have a Dasher personally, so I can’t speak to what you’ve seen … but it does seem to stand in contradiction with what others are saying. You might go read that post and see if there is just a disconnect in how you’re understanding it. Maybe you got a really hard barrel too, I’m not sure.

Thanks,

Cal

Easily one of the best written, most informative, easy to understand collections of data I’ve read. This is up there with Mr. Tubb and Mr. Zediker works. WELL. DONE. By all involved. Sincerely Thank You.

Wow, Gabe! Thank you for that compliment. We really appreciate it!

Thanks,

Cal

Cal, thanks for this series. Yesterday was the first time I’ve tried a test with 20, 40, 60, 80 thousandths of an inch away from the lands, a variation on your article and Berger’s website suggestions. Man were the results interesting. My previous 600yd match load for .223 Rem 80.5 Berger fullbore grouped 5 shots at 1.22″ at .020″ from lands, which is usually my starting depth for any bullet. .040″ grouped 0.66″, .060″ expanded drastically to 1.42″ and .080″ shrunk down to 0.78″ group. I did a similar test with 75 grain Hornady ELDM. There was some variation in group sizes but not as drastic as this Berger projectile.

The whole test was very eye opening and will change my approach to load development going forward. Lately I’ve been hearing from a lot of experienced shooters that you should tune the seating depth first then work powder charge. That’s what I’m going to do in the future, starting with a likely good powder weight, find a good depth and then run an ocw test above and below that powder weight with whichever seating depth looks best. Thanks again for sharing data driven precision rifle knowledge.

That is VERY interesting, Tim! Thanks for sharing, and I’m glad you found all this interesting and helpful. I appreciate that you went out and tried it for yourself! It sounds like you already found some improvements to your match load!

I am right there with you, buddy. This was just as eye-opening for me as it was for anyone! I mentioned this in the comments of another post, but in full disclosure … I actually paid Mark to chamber me two barrels for my 6mm Creedmoor rifles at the end of 2019, and I got him to short-throat them … because I wanted to try the new Hornady 110 A-Tip bullets and I wanted to be able to seat those close to the lands and continue to seat them out as the barrel eroded to keep them close to the lands and still stay within magazine length for the entire life of the barrel. So I asked him to chamber them with 0.100″ of freebore instead of the 0.183″ SAAMI spec. Doh! I hadn’t seen all of this data at that point, but I sure wish I could undo that decision! The SAAMI freebore would have given me about 0.080-0.100″ of jump, but now my lands are too close to even test jumps that are very long. So, obviously I was part of the camp that believed in touching the lands or jumping 0.020″ max! I’ve thought about sending it back and paying to get the freebore extended, but honestly I shoot out barrels fast enough … I’ll just keep going with these and do something different on the next ones.

I definitely think I’m going to start approaching load development just as you described. Find the jump that seems to produce the best groups, and then move to powder tests. However, instead of the OCW test, I might just focus on finding consistent muzzle velocities (i.e. low SD’s) when I am looking at powder charges. I’ve used the OCW test a bunch of times over the years, but Scott’s approach to load development definitely has me intrigued. I might at least try it that way once and see what happens.

Thanks,

Cal

Maybe I’m thinking of this wrong, but does this mean that potentially when a barrel seems like its “shot out” you might just be entering a high variance jump distance range and if you keep shooting it could eventually get better groups as the throat continues to wear out?

This assumes your initial jump distance was very small – based on your variance chart.

Sean, that’s an interesting thought. It probably depends on what someone defines as “shot out.” Often times on my barrels, when I decide to replace them it’s because the muzzle velocity has become inconsistent or unpredictable. Over time the muzzle velocity will start to decrease, and in my experience it starts doing that rather slower, but then it gets to a point where the velocity might drop 25 fps or maybe even a little more over 100 rounds. That means you can’t have confidence to go a whole match, and you’re always wondering if a miss was because your muzzle velocity … and to me life is too short to try to get that last 10% of barrel. If you don’t have confidence in it, replace it.

However, I’d say that is how it happens for me the majority of the time for the mid-sized cartridges I mostly shoot (like Creedmoor sized cartridges), but I’ve also replaced barrels on some of my other rifles because groups opened up. I did that on a 300 Norma barrel last year. I just couldn’t get it to group well. I even tried to do load development on it again, and never could get it under 1 MOA … so I replaced the barrel at just 600 rounds. But, you are making me wonder what would happen if I would have tried to vary jump. I don’t think I did that when I redid the load development at the end of it’s life. I actually still have the barrel, so one day I may dig it out and reinstall it and go see what happens. You certainly made me think about it! My gut would be that is definitely plausible, but I don’t think jump would change the muzzle velocity consistency issue I mentioned in the first paragraph … but it could affect the group size issue, and if that’s the reason you are about to toss a barrel, it’s certainly worth trying different jumps to see.

Thanks for sharing the thoughts, Sean. I bet this is something I’ll think about until one day I break down and go see what happens on that old 300 Norma barrel!!! 😉

Thanks,

Cal

what neck tension who you use for a 6×47 lapua 0.003 dosnt seem like much

Not sure if that’s a question, but I’d bet 90% of precision shooters who handload and pay attention to neck tension target either a 0.002 or 0.003″ of neck tension. That is actually normal, not light. Here is how Bryan Litz defines different levels of neck tension in Modern Advancements for Long Range Shooting Volume II:

I hope that helps. That book provides a good overview of neck tension and some research to see what produces the most consistent muzzle velocities. I’d highly recommend it.

Thanks,

Cal

Hi Cal,

I think this series has been very interesting to follow.

My question though relates to testing bullet seating depth at distance…

Wouldn’t SD/ES influence the results? i.e. if SD/ES aren’t very good, there will be vertical dispersion anyway.

If so, surely adjusting seating depth and therefore changing pressure (and velocity) could have a negative (or positive) effect on SD/ES and therefore the results of the seating depth testing?

Thoughts?

That’s a good question, Jeremy. The short answer is that is probably plausible, and that is exactly where I went early on when Mark started sharing this data with me. I actually thought shooting at 600 yards might be introducing noise into the data, and really you could probably just look at muzzle velocity instead of point of impact, because that was likely what was driving the change in POI. But, after some analysis the changes in muzzle velocity don’t completely account for the change in POI. I won’t say there wasn’t some correlation, but it wasn’t as direct or cut-and-dry as I originally thought it would be.

But, I certainly can’t say that what you’re saying isn’t true … maybe even to a large extent. I actually don’t think Mark’s research data can answer your question, because there was just one shot fired at each jump with each rifle/load configuration. So you can’t really tell what the SD/ES is for different jumps. You really can’t even do it for a range of jumps (like a 0.010 or 0.020 inch window), because there aren’t enough shots within that window with the same rifle/load configuration to have a sample size to derive SD (in my opinion).

I did go back and calculated the SD for the muzzle velocities recorded for the 105 Hybrid test data over all 20 shots with each rifle/load configuration in Mark’s 20-shot jump test, and even over a 0.100″ change in jumps the SD’s for all 10 tests landed between 6 to 14 fps. Which if you think about a 20 shot string that you’re changing the bullet jump by that much, that seems like a pretty small SD.

But, your point is valid. Adjusting the seating depth theoretically adjusts the chamber pressure, which should theoretically adjust the muzzle velocity … so there could be a “sweet spot” in all that you could “tune” too, and maybe that is part of what is going on here. Honestly, I’m not sure what underlying phenomenon is driving this … I’d bet it is multiple factors that likely have some complex interdependence. All I know is the end effect, which is why I became convinced that looking at the actually POI shift at distance likely was the best way to capture the full impact of what was going on. Some might be velocity, some mechanical precision, some the ways pressures build in the chamber, maybe tuning of harmonics, and maybe even other things. Like most good research, it usually uncovers more questions than answers!

I appreciate you sharing your thoughts!

Thanks,

Cal

Cal,

This is fantastic information, it’s very compelling because it’s so deeply researched. Great job.

It seems like the method of the jump testing is closer to ladder testing than OCW in the sense that the testing is done at relatively long ranges to accentuate the differences between test cases. Unfortunately not everyone has ready access to a 600 yard range. Can you think of a way that this could be adapted to shorter distances and still produce useful data?

Thanks, Andrew! Glad to know you found this helpful. And that’s a good question. I’m sure I don’t represent everyone’s view, but I think you can do this at 100 yards if you’re very careful. The results might not be as “conclusive” … but I think you will find enough to make a good decision.

How I would suggest doing it is running through the bullet jump test. Your target should be a grid or at the very least have several different fine aiming points. The target might look like what Aaron Hipp used in the image below:

Personally, I’d load up at least 5 rounds for each of these jumps: 0.050″, 0.070″, 0.090″, and 0.110″. I would fire one of each jump at each aiming point, and then repeat that 5 times. I wouldn’t fire all 5 rounds of one jump and then 5 rounds of another, but instead do a round robin style to keep fouling or barrel temp from possibly affecting the results for some more or less than others. Personally I would fire each string of jumps at different aiming points (i.e. there would only be one bullet impact per aiming point, meaning I’d never fire at the same aiming point twice). You could fire 5 shot-groups for each jump, and it might work just as well or even make it easier to compare – but that’s not how I’d personally go about it. My goal would be to create a chart like the example I mocked up below, which shows the vertical distance from the bullseye for each jump over the all 5 strings. Each dot basically indicates where the bullet hit on the target. In this example, I’d say the black line which is for a 0.090″ jump appears to provide the most consistent vertical.

If you’re doing this at 100 yards, and trying to make decision off relatively small patterns in POI, I would strongly, strongly recommend double and triple checking your parallax. That could add noise to the data and lead to bad decisions, and I think that’s especially true at short range. I also think you need to see patterns over at least 5 shots per jump, and it might be wise to run through this 6-7 times … depending on how noisy the data appears to be.

As I mentioned in the post, I haven’t personally spent a lot of time integrating this into my load development yet, so this is just how I’d approach it based on my limited knowledge if I couldn’t fire beyond 100 yards. I do think you could get data that was good enough to make a decision on with this approach. One upside of short range testing is there is less of a chance that environmentals like wind are adding noise to the data. Of course, if you did all your load development on a calm or even a day with consistent winds, you can mitigate that … but I only point that out because it’s not all bad at short range.

I will say that I feel like sometimes guys aren’t as careful in their aiming at short range, and that’s why some people group better at long range. So I’d be very deliberate with your shots. As always, don’t pull the trigger until your sights are dead center on the target, right?! 😉

Hope this helps!

Cal