When shooting targets at extreme distances (like 2000+ yards), you’ll quickly uncover some new obstacles. A few factors that could be safely ignored inside of 1000 yards become critical to getting rounds on target. You’ll also be faced with new equipment challenges that may not be obvious. As your bullet’s time of flight extends up 3 seconds, and possibly even up to 6+ seconds, priorities shift. You could say everything is important, but to differing degrees.

In the last post, I focused on two big issues related to optics, and highlighted several new products designed to help you overcome those obstacles. In this post, I will summarize significant challenges related to spotting and ranging you may have to address when shooting targets at extreme ranges.

1) Very Difficult To Spot Impacts

It’s very difficult to spot hits or misses at extreme long range. If you don’t see the bullet splash, you don’t know how to correct to center subsequent shots. But, if you spot a miss and see it was 0.5 mils left, and 0.2 mils high of center … apply those corrections and send the next shot. Believe it or not, this is one of the biggest reasons guys use big calibers, like 375 or 416. There are a few 30 and 338 caliber bullets with super-high BC’s that can be launched at blistering speeds, but one reason you don’t see those much at ELR competitions is because it is hard to spot impacts. In fact, I asked a few veteran shooters at King of 2 Miles why they switched from a 375 caliber to a 416 Barret, and they all said it was to make it easier to spot impacts and make corrections with confidence.

Because it can be so difficult to spot your own impacts, some competitions are based in a team format with a dedicated spotter behind a large spotting scope calling corrections for the shooter. If there is bare dirt or sand around a target, it’s easier to spot. But if the target is surrounded by foliage or large boulders, it can be much harder! That’s why a few spotters may even use high-end thermal imaging cameras to watch bullet trace!

Because it can be so difficult to spot your own impacts, some competitions are based in a team format with a dedicated spotter behind a large spotting scope calling corrections for the shooter. If there is bare dirt or sand around a target, it’s easier to spot. But if the target is surrounded by foliage or large boulders, it can be much harder! That’s why a few spotters may even use high-end thermal imaging cameras to watch bullet trace!

To help identify and score hits, it’s common to see target hit indicators, like the MagnetoSpeed T1000. I picked up one of those off the prize table at the HeatStroke PRS match recently, and was surprised to see the batteries in that product will last up to a year! I was thinking you might have to drive out to the target and turn it on/off for every shooting session, but that definitely changed my view of how convenient those can be.

Some competitions use wireless camera systems to spot impacts down range. At the King of 2 Miles they had wireless cameras on every target that allowed you to watch impacts down range in full HD with virtually no latency. There was no doubt whether someone connected with the target or not. They even had a spectator tent setup with a big screen TV where you could watch the same live feed the scorers were. It had to be the most advanced camera setup I’ve ever seen. The Ko2M wireless camera system was built by Alexander Cordesman, and you can find him on Facebook if you’d like more details.

2) Getting An Accurate Target Range

“When using a well performing rifle and ammunition, the uncertainty in the range measurement is the single largest contributing factor to the vertical uncertainty in a given shot and drives the overall probability of hitting the target,” explains laser expert, Nick Vitalbo. While that is true for all long range shooting, it is even more important in ELR. As distance increases, having an accurate range becomes more and more critical, but it also becomes harder and harder to obtain at the same time!

Very few consumer-grade laser rangefinders can reliably range 2,000+ yards in typical, bright daylight conditions. And even if one gives you a reading, how accurate is it? Most rangefinders only claim to be accurate to within 0.5% beyond 500 yards, which means even if they get a range at 3,000 yards it could be off by +/- 15 yards. That could result in a shot being off-center by 7’, even if everything else is perfect! I conducted a massive rangefinder field test a few years ago, which is the only published study I’m aware of that analyzed the accuracy of the readings that each rangefinder produced. That study made it clear that there can be a big difference in the accuracy depending on the rangefinder you pick. A summary of the results are provided below, but you can view the results for the rangefinder field test here.

You can see in the chart above that a few of the rangefinders might give you a reading for the distance, but it might be wrong by more than 1% a lot of the time! Remember ealier I mentioned +/- 0.5% could make you be 7′ off-center, but the red bars on the chart indicate the range was off by more than 1% … so your shot could be off by more than double that! Obviously, not all rangefinders are created equal.

When it comes to high-end rangefinders, Vectronix is the gold standard that everyone else is compared to. Of course, the Wilcox RAPTAR is another rangefinder capable of extreme range. But don’t take my word for it! The chart below shows results from the most in-depth rangefinder test ever conducted, which was published by Nick Vitalbo in Modern Advancements in Long Range Shooting Volume II. Nick the one of the foremost laser experts in the world, and if you’re interested in learning more about this topic, I’d highly recommend reading his study. It is a wealth of information!

Of the 22 rangefinders Nick tested, only 4 of those were capable of consistently ranging to 2,000 meters or more, which were various models of the Vectronix PLRF and Wilcox RAPTAR. Nick only tested ranges out to 2,000 meters, but he did say “a number of the laser rangefinders greatly exceed that value, especially the PLRF devices from Vectronix.” For reference, my Vectronix PLRF 15 can range to 4,000+ yards.

Bryan Litz sums it up for us:

“Bottom line: unless you have access to a high-end military laser rangefinder, determining the exact range to target will be a significant problem for ELR shooters.” – Bryan Litz, Applied Ballistics for Long Range Shooting, 3rd Edition

So what makes military-grade rangefinders so much better? There can be a few things, but the biggest difference comes down to the power of the laser. The key to getting an accurate range is to get enough energy on the target, so that it will be reflected back to the rangefinder and the device can separate the signal from the noise. A massive, instantaneous pulse of energy is ideal. A military rangefinder might produce a pulse with 100,000 watts of peak power, compared to 10-25 watts of peak power in consumer-grade rangefinders. That’s a massive difference! The duration of the pulse is also different, with military rangefinders being just 4-5 nanoseconds and consumer-grade being close to 100 nanoseconds (i.e., the duration of the consumer-grade pulse is 20 times longer).

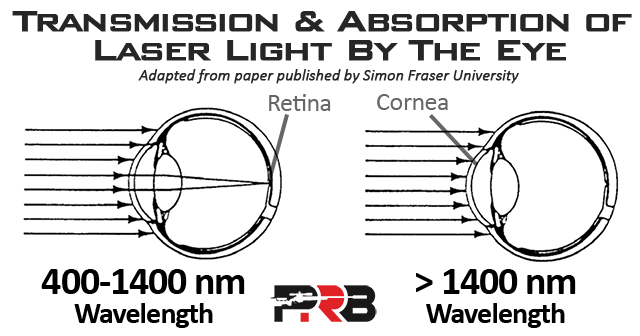

The next question might be, why don’t consumer-grade rangefinders use more power? A big reason is eye safety. Lasers with a wavelength in the 400-1400 nanometers (nm) range can travel through the eye and do direct damage to the retina, potentially causing permanent injury and blindness. Consumer-grade rangefinders are based on a 905 nm wavelength, which is invisible and falls right in the middle of that dangerous range. So for those rangefinders to be rated as “eye safe” manufacturers must limit the power they emit. On the contrary, military-grade rangefinders are based on lasers with a 1550 nm wavelength, so they don’t pose the same threat to eye safety because wavelengths longer than 1400 nm are absorbed by the cornea and don’t make it to the retina. That means 1550 nm rangefinders can use higher powered pulses and still be considered eye safe. (Learn more: Source 1, Source 2)

While consumer-grade 905 nm rangefinders use low-powered pulses, they try to make up for that by sending out multiple pulses, perhaps up to 100,000 pulses per second. Although the rangefinder receives a lower amount of light back on a pulse, it collects and analyzes a large set of data to help it separate the signal from the noise. That is a clever statistical trick, which explains why consumer-grade rangefinders are able to perform as well as they do. However, this approach still doesn’t get close to the performance capability of military-grade rangefinders that can send a concentrated pulse with much more energy in a very short amount of time, and still be eye safe. Nick says, “There is no substitute for raw laser power when it comes to designing a laser rangefinder.”

While consumer-grade 905 nm rangefinders use low-powered pulses, they try to make up for that by sending out multiple pulses, perhaps up to 100,000 pulses per second. Although the rangefinder receives a lower amount of light back on a pulse, it collects and analyzes a large set of data to help it separate the signal from the noise. That is a clever statistical trick, which explains why consumer-grade rangefinders are able to perform as well as they do. However, this approach still doesn’t get close to the performance capability of military-grade rangefinders that can send a concentrated pulse with much more energy in a very short amount of time, and still be eye safe. Nick says, “There is no substitute for raw laser power when it comes to designing a laser rangefinder.”

Why aren’t all rangefinders based on high-powered 1550 nm lasers? Simple: cost. To be able to produce that quick, high-powered pulse, many military rangefinders use diode-pumped solid-state lasers (DPSSL), which are more expensive than the common 905 nm diode lasers used in consumer-grade rangefinders. But it’s not just the laser that is more expensive, the material and amplifier circuitry needed to detect the reflected light in the 1550 nm wavelength also adds significant complexity and cost. That’s why military-grade 1550 nm rangefinders are all priced over $5,000.

The truth is, there hasn’t been a big civilian market for extreme long range rangefinders up to this point, because 905 nm rangefinders are easy to manufacturer, a fraction of the cost, and accurate to distances beyond what 99% of people will ever shoot to. While the number of people shooting to 1 mile or more is growing rapidly, it is still a relatively small crowd. I realize if you’re reading this you’re interested in it … but apparently we’re not normal! 😉

Note: If you find this as interesting as I do, I’d highly encourage you to read Nick Vitalbo’s comprehensive explanation of how rangefinders work in Modern Advancements in Long Range Shooting Volume 1, and then read his epic rangefinder test and analysis in Modern Advancements in Long Range Shooting Volume 2. Both are very interesting, and cover many other factors that impact ranging performance that I didn’t mention (i.e. beam divergence, beam shape, how atmospherics and target surface affect performance, what happens if it gets multiple readings. You can buy both books in a bundle and save a little money.

I’ve personally been using a Vectronix PLRF 15 for a few years (replaced by the PLRF 25), and it is a ridiculously outstanding rangefinder. I’ve used it to get ranges out to 6,500 yards on distant hillsides, which is 3.7 miles! To make it even more unbelievable, that was done in bright, mid-day conditions. I’ve used it to range 1,000+ different targets, and can only remember two times when it wouldn’t give me a reading. Both of those were when I was trying to range a steel target that was sitting very low in a grass field. They were on the crest of a hill, which made it even harder (thanks Scott Satterlee!).

If you haven’t noticed, I’m a pretty critical guy – some might even claim I’m impossible to please. But, I’m not sure I could have more confidence in a rangefinder than what I have in my Vectronix PLRF. It is one of those tools you just love to reach for.

Vectronix recently released a new rangefinder called the Vectronix Terrapin X, which a company rep told me was their first official attempt at a product intended for the commercial market. All of their previous products were designed with military customers in mind, which often put the price out of reach for most people. The Terrapin X has a street price around $1,800, which is 80% less than the cost of the PLRF 25! Vectronix sent me a Terrapin X to test a couple months ago, and I’ve been using it A TON! I plan to write a full review in the near future, but my results so far are impressive. It is based on a 905 nm laser, so it’s not a PLRF. But ranging capability is very similar to the original Terrapin, which could mean it’s the most capable rangefinder under $5,000. So stay tuned for more details on the Terrapin X!

Most competitions like Ko2M publish the distances for all targets (i.e. targets are all “known distance”), so you don’t necessary need to own an expensive rangefinder. However, if you don’t have access to one it can make it harder to practice and true your ballistics at your own range. I also prefer to confirm the distances on all targets myself at a competition, even if the distances were provided, because I’ve found match directors may not be as detailed or have high-end rangefinders themselves.

Coming up in the next post, I’ll cover a few more things that make ELR shooting difficult, including the challenges of modeling a bullet’s flight and the different tactics top shooters are using to have reliable ballistics at extreme long range. I’ll share tips on how Robert Brantley, winner of the 2018 King of 2 Miles, calculated his ballistics to get hits out to 3,525 yards, and I’ll also share some of the new advanced methods shooters on the Applied Ballistics team are using to calculate their ballistics. Stay tuned!

PrecisionRifleBlog.com A DATA-DRIVEN Approach to Precision Rifles, Optics & Gear

PrecisionRifleBlog.com A DATA-DRIVEN Approach to Precision Rifles, Optics & Gear

There is no mention of the night time capabilities of the range finders you covered. Do they work at night time?

That’s an interesting question, Michael. Yes, I’m fairly certain they’ll work at nighttime … in fact, I’d bet they work better at night, because there isn’t solar interference. But, it might be hard to see your target at night. I will say that Tier 1 Special Forces have some cool toys that help them range at night (which makes these things seem like small dollars), but that is probably all classified stuff.

Thanks,

Cal

Great post as always Cal! I look forward to your future ones; keep them coming!

Cheers,

Steve

You bet, Steve! I’ve already got the next post mostly written. The biggest thing is trying to explain the more technical aspects of these topics in a non-technical way. I bet I completely rewrote the section of this post about what makes military-grade rangefinders different at least 4 or 5 times. No telling how many hours I spent on that! It’s a balancing act between not providing too much detail, but providing enough to be accurate and not misleading. I probably wordsmithed it to death, but that is something I feel like most guys don’t understand … but is helpful. The next post is the same way. When talking about transonic effects of bullet flight, you get into some really technical aspects that is just one variable short of rocket science! (i.e., thrust) 😉 I’ve already got much of the content and graphics complete for that post, so I hope there won’t be as far of a gap until the next installment.

Thanks,

Cal

First off, thanks for all the hard work you put into your blog. I’ve spent many hours pouring over all the info you’ve provided. You are very respectful, thorough, and kind in your comment section as well. Appreciate all you do!

I have a question on ELR Part 1, but the comment section appears to be closed so I hope you don’t mind me asking here instead.

In the ELR Part 1 article you referenced your previous article on scope tracking. I tried to conduct my own tracking test and have a couple questions. I talked with my scope’s manufacturer (SWFA) when I conducted my tall target test and they said it is nearly impossible to conduct this test in the field and really needs to be done in a laboratory setting. SWFA said “the most common error we see is when the scope they test is pointing uphill or downhill a little and then they get a compounded error of the distance being wrong and the target being at an angle.” In your test you used an accurate distance measuring tool for the distance, a 72” level to make sure the target was perpendicular to the earth (gravity), and checked that the scope tracked along the vertical lines on the target to ensure the scope was vertically plumb as well. I modeled my test after yours; however, based on SWFA’s response to me, I have a couple questions. How can I verify that the target and scope are directly across from one another (i.e. not at a slight angle “uphill or downhill”)? How can I verify that the target (and/or scope) is not at an angle (i.e. tilted backwards or forward)?

I forgot the exact numbers that SWFA mentioned (we were talking in person at the time, so I don’t have email records) but it was something like if, for example, the target was angled 3° back (no longer at a 90° angle to the scope) it would appear that the scope has a tracking error of 1.8%. Unfortunately I was unable to get the info on where they got those numbers and I am not sure how to verify. Is bubble level sensitivity enough to account for this degree of accuracy when setting up the target and scope?

I hope this all makes sense! Feel free to delete my question if I did not post it in the correct area or if this type of question is not allowed (first time posting on your Blog). I really want to conduct a tall target test to verify the tracking in my scopes, but I feel daunted by SWFA’s response.

Great questions, Mick. I don’t mind that you asked them at all. I can tell you’re serious about testing your equipment, which I really appreciate. The absolute best way to make sure it is level between your rifle and the target is with professional survey equipment (i.e., hire a surveyor). That might be a little over the top though. I’m sure there are more pragmatic ways to do it. First, there are many rangefinders that will give you the angle to the target. Another way is with an angle indicator attached to your rifle. Another way that might work is putting a small bubble level on top of your turret or rail, point the rifle at the target, make the rifle level … and see if the target is in the field of view. That way isn’t perfect, because the turret might not be perfectly level. I actually almost attached a simple bubble inclinometer to my spotting scope recently, just to have something to quickly reference for the angle to the target … and I’d think that would work too.

While I appreciate the attention to detail, I’m skeptical that 1-2 degrees of angle from the shooting position to the target would make a measurable difference in tracking. I haven’t done the math, so it might. I do think the target not being plumb to your position could make a difference, and you should be careful with that.

Hope this at least gives you a few options on how to proceed. You might ask SWFA for their recommendation, because if your results aren’t good … they’ll be critical of your methods. So I’ve found it’s best to ask the manufacturer for advice on the test methods.

Thanks,

Cal

Thanks as always, Cal. Very interesting.

Thanks, Matt. I wasn’t sure if this one would be interesting to everyone, or just me! 😉 I appreciate you taking the time to send the encouragement.

Thanks,

Cal

Thank you Cal. This is a great summary and guide for further research. I am a permanent fan of your commitment to providing accurate and useful information in a logical fashion. Please keep it up.

Thanks, Michael. Glad you found it helpful.

Thanks,

Cal

Very interesting Cal,

I had not even heard of the Wilcox yet. Seems like it mounts to the scope? I went to their website and can’t find a max range. Seems like it is in the PLRF price range.

I could not agree more with you on the ranging issue. I realized a few years ago that the most expensive single thing in my kit was the rangefinder, a use a Vector 21. I started with a terrapin and sometimes use it to double check with the 21.

My biggest problem was always the issues with servicing the Vector. Nothing has ever broken down, yet, but I hear some horror stories about sending things back to Switzerland and getting into trouble shipping it back? A few people I know went with the Sig 2400 for that reason.

Sometimes my standard shooting spots are a no go because of various reasons, so I hike a bit further and try and find other targets of opportunity at Panoche Hills in central CA. What I have noticed is if the 21 can’t range it then it’s probably not worth shooting at to begin with- some kind of really bad mirage, etc. It’s like having an expert riding with you and telling you to move on and find something better, it really helps. Sometimes I just cannot tell looking through the scope.

I know a few people that don’t use high end laser- Mark and Sam in Australia use a Sig 2400 and essentially rely on a simple cell phone GPS program, but they are shooting on private land and have plenty of time to set up targets. My situation changes all the time on BLM land, so it’s largely a variable and it needs the laser.

At KO2M I have heard reports of people using thermal binocs (Flir B2’s)? Maybe some advantage to spotting hits? Another story was the use of a Leica Pinpoint R1000, which is some kind of civil engineering surveying equipment. I am at a total loss to explain what the idea behind that is.

Target Vision has a new ELR camera that is very reasonably priced under $1000 that goes to 2 miles, something that is definitely on my list of things to try.

Yes sir. The Wilcox RAPTAR is intended to be cowitnessed with a scope (either mounted on a rifle or a spotting scope). There isn’t a viewfinder on it, so it can’t be used stand alone like the PLRF (Pocket Laser RangeFinder). After you have it cowitnessed with the reticle on your scope, you just push a button and it displays the range to whatever your reticle is covering. There is a version with the Applied Ballistics engine built-in, so it can also automatically display the firing solution too … which is VERY sweet.

Wilcox publishes a max range of 1500 meters on a 0.5m x 2.9m with 50% reflectivity, but I’d suspect you could range must further. In Nick’s tests, he showed it was capable out to 2,000+ meters. Vectronix also advertises a max range that is much shorter than you can actually expect. It’s kind of the opposite of consumer-grade rangefinders. Honestly on commercial rangefinders, if the model has “2000” in the name … you can typically just cut that by 30-50% for what to expect in real-word conditions. Vectronix and Wilcox both seem to be under-promise/over-deliver type companies.

And I’ve never had to use the Vectronix service department. I have a buddy with a Vectronix Terrapin, and he’s never had issues with it either. Honestly, these devices seem to be built like a tank. My PLRF 15 certainly is. I think they switched to a polymer housing for the PLRF 25, but I’m sure it’s durable too. You know some companies stamp lifetime guarantees on things, and staff up their service departments for quick turn-arounds … but I’d prefer to have a product I never have to send in to service. It reminds me of a scene from the movie Tommy Boy where Chris Farley says something like “I could take a crap in a box and mark it guaranteed if it makes you feel better. I have the time.” 😉

You can certainly get close with GPS, if you take the time to carefully gather the information. I believe you will have about +/- 10 feet of error on both ends, so it’s not perfect … but close. The Sig Kilo is a great rangefinder, especially for the money. Sig is serious about the optics market, it seems. However, it looks like Nick’s tests only had the Sig Kilo able to range out to 1400 meters on the 30″x30″ target, so it may not be a great option for real ELR shooting.

And yeah, that photo in the post of the thermal imaging device and monster binoculars was of David Tubb at King of 2 Miles. The Applied Ballistics team also used a thermal imaging device last year, but there was a knew rule that you couldn’t gather measurements downrange. I think that was intended to mean you couldn’t have equipment taking wind or environmental measurements, but the AB team thought that meant you couldn’t use thermal imaging either, because technically it is gathering info downrange. They didn’t use one this year to be above reproach. They did tell me it can work well if it isn’t too hot outside. And I’ve seen them use a Leica Pinpoint R1000 in their lab, but not out in the field. I guess when you just really have to know the range with surgical precision, maybe that is where you should go. It’s funny that we’re getting all the way to advanced surveying equipment! That’s awesome.

I appreciate the comments!

Thanks,

Cal

Hey Cal,

Do you know what the purpose of the thermal stuff is? You mentioned getting info downrange, does that mean looking at air and determining if it is rising or falling? Kind of a way to read mirage more objectively? Or does it help with the actually spotting, meaning some kind of thermal imaging picks up dust / impact effects?

I see that cool shot of David Tubb and the big eyes but still wonder what exactly is going on there!

You are actually watching the bullet trace as it flies to the target. Apparently you can see the heat signature off the bullet, similar to if it were a tracer round. Where it is really helpful is if there is vegetation all around the target. If you miss the target and your spotter is using a traditional spotting scope … you won’t have a clue where you missed. In that case, you’d send another shot blind … which is not good! But if your spotter is able to watch the trace as bullet approaches the target, you might get an idea of whether you missed high/low or left/right, and then make an educated correction for your next shot. You don’t have to see the bullet splash to get that feedback, because you’re watching the bullet flight. In some of these competitions you might just get 3 or 5 shots on a target, and if you don’t connect you are out. So spotting impacts for second shot corrections is a HUGE part of this game.

But, I will say none of the guys who finished in the top 10 at the 2018 King of 2 Miles were using thermal imaging equipment. It might be helpful, but it also might be a distraction. It’s clearly not necessary to be competitive. It was just something I thought was interesting. I don’t personally own one and don’t have any plans to purchase one either. I personally see a military-grade rangefinder as equipment that is VERY helpful … but thermal imaging seems superfluous.

Thanks,

Cal

I wonder how the new Nikon 4K stacks up to these range finders.

I wish I knew. My first rangefinder ever was a Nikon, but that was a decade ago. That is a 905 nm rangefinder, so I’d be surprised if it was capable of ELR distances. But it might be a great rangefinder for traditional long range distances.

Thanks,

Cal

I had the chance to test this out recently. It was around 1100 yards for a 20% reflective target that is 2.5ft x 2.5ft. Additionally, it ranged to 1600 yards on a 50% reflective target of the same size. In other words, comparable to the KILO2400 units.

That’s awesome, Nick. I appreciate you chiming in!

Thanks,

Cal

Hey Cal another good post. Learned a lot from your blog. When do you think youll write another article updating us on what the pros are using in competition as far as cartridge selection and barrels? Also for someone starting ELR, an article on how to load develop for cartridges like 375, 408, or 416 or is it the same as you would do for a regular bolt action rifle chambered in 6mm , 6.5mm, and etc

Hey, Anthony. I hope to do the What The Pros Use again at the end of this season, if the PRS or NRL guys will allow me to gather that data and publish it. And honestly, I’ve never done load development on a big bore cartridge … so I’m not sure. I’ve ordered an ELR rifle, but don’t have it yet … so I haven’t got there. I may actually buy ammo for that rifle, at least at first. I doubt I put thousands of rounds down it like I do on my other rifles, so I might skip the whole load development thing … or at least bypass it for a moment upfront. Sorry I couldn’t be more help!

Thanks,

Cal

For hunting or preparing before a PRS match I feel the current (2018) Leica HD-B rangefinder/calculator with its suite of sensors and removable and programable Micro SD ballistics card is an excellent piece of gear. It covers themaiimum ranges I will be shooting in any foreseeable situation given the limitations of my 6.5 CM cartridge. Add a Kestrel/AB 5700 and I’ve got not only some wind hold but a comparison on the vertical hold.

Maybe if I add a 6.5 PRC rifle to my quiver I could justify a better LRF but that is at least a year in the future.

As for 2 mile shooting, well I’m content to just sit back and read about the competitions.

QUESTION: Will LRF makers ever get to the point that their rangefinders have a full suite of sensors to work with an AB style ballistics program AND a “plug-in” anemometer for a complete firing solution? Just asking’…

Eric, that Leica HD-B is an amazing piece of gear. It is what I personally carry all the time hunting and sometimes to PRS matches too. The ballistic engine is based on a pre-calculated table (at least the original version of it was), and that table is skewed one way or the other based on the environmentals. That works for mid-range shots, but it might not be as precise for targets way out there. Devices like the Kestrel/AB 5700 don’t use pre-calculated tables, but do the real calculations on the fly, so I’ve found them to be fairly reliable out to where the bullet gets near the speed of sound.

And today is your lucky day! I’m happy to say there actually is a rangefinder with a suite of sensors, the AB ballistics engine built-in, and a “plug-in” anemometer. It’s the Sig Kilo 2400 ABS. It’s a very capable device in a compact package. Check out where it lands in Nick’s rangefinder test chart above. Very capable device!

Thanks,

Cal

thank you verry much , you have lot of luck to practice shooting in america you have the best material and the best champion and your country is verry wonderfull

my GOD bless you .

Thanks, guisiano. I appreciate you reminding us how great we have it. It’s a real privilege to have the freedom and access to get to do things like this for fun. It’s easy to take for granted when it’s your everyday reality, but I’ve traveled enough to know most countries don’t allow private citizens to have this much fun with guns. We still have a lot of issues in America, but it’s a wonderful place and we’re blessed to get to enjoy the freedoms we do. Thanks for that reminder!

Thanks,

Cal

Any LRF/Solutions computer that co-witness on a diving board you would recommend in 2025 that’s not 10,000 dollars? Thanks

Denny, I don’t have much to offer. The Vortex Impact 4000 Ballistic Rail-Mounted Laser Rangefinder is the only one I know of guys using that fit that budget … but I don’t have any direct experience with it. Sorry I couldn’t be more help!

Thanks,

Cal