This is the 3rd post in a series covering the results from an epic scope field test focused on long-range, tactical rifle scopes in the $1,500+ price range. This represents an unprecedented, data-driven approach to evaluating the best tactical rifle scopes money can buy. Hundreds of hours have gone into this research, and both the scope line-up and the tests I conducted are built on advice and feedback from some of the most respected experts in the industry. My goal with this project was to equip fellow long-range shooters with as much hard data as I could reasonably gather, so they could see what they’re paying for.

This post is focused on scope ergonomics, and the overall experience behind the scope. This includes things like weight, size, eye relief, and turret design. In Part 2 of the ergonomics results, I’ll go through each scope and point out the unique features of each, include videos that demonstrate the scope from the shooter’s perspective, and also include a full photo gallery for each scope with shots of every angle.

Do Ergonomics Really Matter?

With scopes, you’re often trying to strike the right balance between optical performance and weight/size. This same tug of war occurs with binoculars, telescopes, and other optics. If weight and size doesn’t matter, why don’t more competitors and hunters look like these guys?

Note: These aren’t spoofs … they’re both real products. In fact, the scope is in the same line as the Zeiss scope included in this comparison, except the one in the pic above has a 72mm objective instead of 56mm.

But there are more to ergonomics than just the size of the scope. So we’ll explore some of the major aspects long-range shooters should consider in this article.

Scope Weight

The weight of the optic is a concern for most shooters, especially for those who have to carry a rifle farther than from the truck to the bench. A few of these scopes have been lovingly referred to as a “boat anchor.” They’re the heavyweights, but some are a little heavier weight than others.

It was no surprise that the scopes with the smallest objective lenses (March Tactical 3-24×42 and Leupold Mark 6 3-18×44) were the lightest, with 25% less weight than their nearest competitor. And although the Schmidt and Bender scopes are notoriously hefty … there were a few that topped them including the Nightforce BEAST 5-25×56, US Optics ER25 5-25×58, and Valdada IOR RECON Tactical 4-28×50. But, the big fatty award goes to the Hensoldt ZF 3.5-26×56 weighing in at almost 3 pounds! We already saw there is some quality glass in that body with the optics results, but apparently, it is some heavy glass too.

The chart below shows how much optical performance you’re getting for the weight you’d be carrying. To calculate this, I took the overall optical performance score from my optics review, and divided it by the weight in ounces. This essentially shows how well each scope strikes the balance between those two competing design characteristics.

The scopes with the smaller objectives obviously packed a lot of punch, but notice the next few scopes on the list: Zeiss Victory FL Diavari 6-24×56, Nightforce NXS 5.5-22×50, Kahles K 6-24×56, Schmidt and Bender PMII 5-25×56, and Leupold Mark 8 3.5-25×56. There has to be some kind of mistake! How did a heavy Schmidt and Bender scope get rated well in anything related to weight?! … After double-checking the numbers, it turns out to be true. All of those scopes pack a ton of performance for their weight.

Scope Size

Weight isn’t the only consideration … size and bulk can make a scope cumbersome as well. That’s why there has been a trend recently towards short and light scopes (and we now have the technology to pull that off). The chart below shows what I measured the overall length of each scope, excluding scope covers and sunshades. Note: This could vary slightly based on the eyepiece focus adjustment.

The Leupold Mark 6 3-18×44 and March Tactical 3-24×42 FFP are both ultra-short. The Bushnell Elite Tactical scopes were also short compared to the rest of the scopes in the group. And there is the Hensoldt ZF 3.5-26×56 again … an extremist, never to be seen in the middle of the pack! The Valdada scopes are also very short, and the Nightforce ATACR 5-25×56 is a little shorter than their older designs. For these heavyweights to be under 15 inches of overall length is quite the feat, and a few managed to get under.

The US Optics ER25 5-25×58 was the longest at over 18 inches, which was 1.6 inches longer than its nearest competitor. In use, you could tell it was obviously longer than all the other scopes.

Another aspect that adds to the apparent bulk of a scope is how far it sticks up off the rifle. This can impact maneuverability, and be something that can get hit or caught on something while you’re getting in a shooting position. To quantify this, I measured:

- Max Height: This is how high the scope sticks up above the rifle. It’s the distance from the lowest point on the scope (the bottom of the objective bell), to the highest point on the scope (the top of the elevation turret).

- Max Width: This is measured from the point that sticks out furthest on the left side of the scope to the point that sticks out furthest on the right side of the scope. This is typically from the outer edge of the parallax knob to the outer edge of the windage turret.

You can see the Nightforce BEAST 5-25×56 and Hensoldt ZF 3.5-26×56 will tower above a rifle. Nightforce has a new elevation turret design on the BEAST, which they call the i4F™ Elevation Controls. I’ll talk more about the specifics of this new turret design in the next post, but one of the downsides is the height. It has two additional parts that add to the height, which aren’t on their older designs: 1) Press & twist lock, 2) M2™ Precision Elevation Lever (a.k.a. ½ click switch shown below). Both features add height to the turret, which is why it is ½” taller than 75% of the scopes in this comparison.

Like I said before, the Hensoldt ZF 3.5-26×56 is an extremist. It’s never in the middle of the pack. That is true on virtually every chart for this entire field test … for better or worse. This super-wide scope is over 4 inches wide! Wow … wow. While the Hensoldt was one of the shortest scopes in terms of overall length, it was also one of the tallest and definitely the widest. It’s our rebel! Hensoldt is certainly challenging the status quo on many fronts with this new design.

Some of the other scopes that were wider than typical include the Valdada IOR RECON Tactical 4-28×50, Steiner Military 5-25×56, Valdada IOR 3.5-18×50, Nightforce ATACR 5-25×56, and Schmidt and Bender PMII 3-27×56. Like weight, this usually wouldn’t be a reason to rule a scope out … but it can be a downside in some scenarios.

Eye Relief

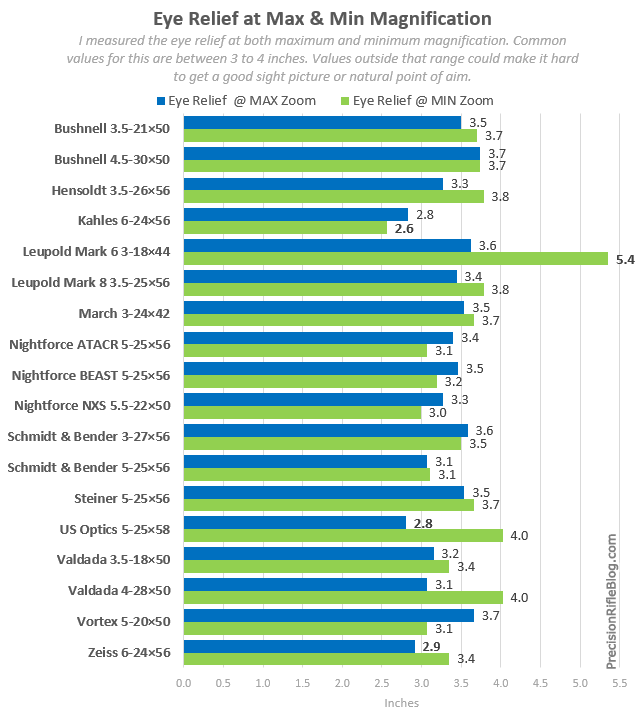

Did you realize a scope’s eye relief often varies with magnification? Manufacturers typically only publish one measurement for eye relief, which leads most consumers to believe it’s always that distance. Ideally, eye relief would be the same at all magnifications, but that simply isn’t always the case. If eye relief varies significantly, it can make it very difficult to maintain your natural point of aim. Natural Point of Aim (NPA) is critical for connecting consistently at long-range and all forms of precision shooting.

I measured the eye relief at the min and max magnification for each of the scopes. And in the continued tradition of complete transparency of how I gathered the data, the video below illustrates how I measured eye relief.

Most scopes have an eye relief between 3 to 4 inches, but values that fall outside that may not be a problem. While the specific eye relief distance can be important, you often have room to adjust the scope to your natural point of aim by moving the mount on the rifle’s rail, and/or moving the scope within the mount. However, if the eye relief varies significantly based on magnification … the only option is to compromise your shooting position and/or sight picture.

One thing I was hoping to quantify is the “eye box” of a scope. Some scopes are just more forgiving in terms of eye relief, meaning slight movements of your head (up/down, left/right) don’t result in a limited scope picture. I couldn’t come up with a way to objectively measure this. However, I did want to mention many testers felt noticeably more comfortable behind the Hensoldt ZF 3.5-26×56. Its eyepiece design seemed to provide a larger eye box, which made it much easier to maintain a full field of view behind the scope. I did notice the Hensoldt’s eyepiece was 20% larger (in terms of area) than the average scope in this test, which could be related.

How Easy Are the Turrets to Use

Some people prefer turrets that are easy to adjust, because they don’t like feeling like they’re having to fight with the scope when they’re laying behind it prone. There are already enough things on our mind in that moment. Other shooters prefer their turrets to be a little stiffer, to reduce the odds they’ll accidentally move it if they rub against something when they’re on the move. And some guys prefer MTC (More Tactile Clicks) for a more positive feel of the clicks, which should help you make adjustments without having to look at the turret (can make an adjustment in pitch black or without lifting your head off the scope).

There isn’t a right answer here, this is all personal preference. But since this aspect of ergonomics is a big part of the experience behind of a scope, I wanted to quantify where each one fell on this spectrum. If have you access to one of these scopes, it should give you an idea of what the others feel like relative to the one you know.

I was originally researching specialized meters to measure this, but torque is relatively easy to measure directly (if it is torque arising from a perpendicular force, which is what I’m looking for). I used clamps and trigger pull gauge to determine the amount torque it takes to adjust the elevation turret on the scope.

Here’s the equation for the magnitude of a torque, arising from a perpendicular force in the same plane of movement:

Torque (inch-pounds) = distance from twist point to weight (inches) × weight (pounds)

So here are the results. Notice a few of the scopes had More Tactile Clicks (MTC), which means they were slightly harder to turn on specific clicks. For example, to adjust the scope from zero to the 1st click required more force than turning it from the 1st click to the 2nd click. Some people describe that as it feeling “sticky” on certain clicks, which is part of that tactile feedback that they’re trying to provide shooters. That allows them to be aware of where they’re at on their adjustment without having to visually check the turret. The Hensoldt ZF 3.5-26×56 and the Schmidt and Bender PMII 3-27×56 were “sticky” on every whole number (1 mil, 2 mils, …), and the Leupold Mark 8 3.5-25×56 was “sticky” on multiples of 5.

In a conversation with one manufacturer, they said the reason some scopes are more difficult to adjust is because of the rigorous military specifications they must adhere to. Simply put, the cost of mil spec is often a loss of ergonomic feel. When you add tight o-rings to turrets to waterproof the scope to a certain depth, the adjustments will lose some of the light, tactile feel. So that is just another competing design characteristic all these guys are trying to figure out.

Turret Size & Design

There are a ton of different turret designs and sizes, and the photo below shows a couple examples. Once again, this is all about personal preference. But the turret can have a big impact on how much you like the scope, because it is the part you probably touch the most. So I wanted to quantify some of the differences to help people make informed decisions.

One important aspect is the size of the numbers on the turret. I want to be able to easily read the numbers on the turret. I don’t have particularly bad eye sight, but I’d like to reduce the chance I misread it in the heat of the moment. I’d also like to minimize how much I have to strain to read it or lift my head to see it properly. The chart below shows the height of the numbers on the elevation turret of the models I tested. The scopes shown above are the ones at the extremes of this chart.

The turret dimensions are also important. I personally started to lean more towards a wider and shorter turret as I went through this field test, like the size found on the Valdada IOR scopes, US Optics, March scopes and others. You can still fit a lot of clicks per revolution, but they don’t have to be packed so tightly together.

The chart below shows how many clicks of adjustment each scope had per revolution of the elevation turret. Most of these scopes had 0.1 mil clicks. The March Tactical 3-24×42, and Nightforce NXS 5.5-22×50 scopes I tested had 0.25 MOA clicks, although these are also available in mil adjustments. The Nightforce BEAST 5-25×56 I tested was the MOA version, but it had 0.5 MOA clicks. That is because of a new turret design feature that allows you to flip a switch on the scope to add 0.25 MOA of adjustment. The Nightforce BEAST is also available with a mil turret, but that version has 0.2 mil clicks with a similar switch to add 0.1 mils. I cover that more in-depth later in the ergonomics section focused specifically on the Nightforce BEAST scope. The adjustments on the Zeiss Victory Diavari 6-24×56 scope were 0.25” clicks at 100 yards, or what is more commonly referred to as “Shooter’s MOA.” That isn’t the same as “true” MOA, but it is close. 1 MOA at 100 yards is 1.047”, and 1 Shooter’s MOA is exactly 1.000” at 100 yards. Not all ballistics engines support Shooter’s MOA, so that could cause issues (or at least confusion).

Wow … the Hensoldt scope. I’m getting tired of talking about it! Do you think they tried to break all the rules with that scope? The Steiner Military 5-25×56, Kahles 6-24×56, and the Schmidt and Bender scopes all packed in a lot of clicks per revolution. Most shooters would probably never need to adjust into the 2nd revolution on those scopes, which can actually help prevent a lot of mental errors. With my 6XC rifle, I can stretch out beyond 1350 yards (3/4 of a mile) and still be on the 1st revolution of these scopes. I’ve missed shots before because I got lost on what revolution I was on (its a very frustrating moment), so having a lot of clicks per revolution can help that (or just being smarter than me). Also considering the Nightforce BEAST has larger click values than the other scopes, it easily gives you that same advantage.

The Vortex Razor HD 5-20×50 I tested was the version with 5 mils per rotation, but they also have an option for a turret with 10 mils per rotation. So that would double the amount of clicks per revolution, and put it into that 100 class. If you commonly shoot beyond 600-800 yards, you might prefer the 10 mil version so that you aren’t getting up into the 2nd or 3rd revolution. However, if you typically stay under that range the 5 mil turret is actually a great option because it gives you lots of control, and its really easy to see what adjustment you’re on.

There was also a significant difference between how tightly packed the hash marks were on each scope. If the adjustments were really packed together, it can be more difficult to ensure you’re on the adjustment you mean to be. It can be hard to differentiate between lines so close together. You also need good fine motor skills to be able to flip directly to the adjustment you’re intending, without overshooting it accidentally. I refer to this attribute as the “click density” of a turret. I completely made that up, but you can look at the image below to see what I mean.

To calculate the “click density” I first measured the diameter of the turret using digital calipers. I measured the part of the turret where the numbers are located. Then I calculated the circumference of the turret (simply the distance around the turret). Then I took the number of clicks per revolution and divided that by the circumference. The chart below shows the results. The scopes at the extreme ends of the chart are the ones pictured in the image above, to help give you an idea of the spread.

Well, there’s the Hensoldt ZF 3.5-26×56 one more time at the top, with a ridiculous amount of clicks for its turret size. Honestly though, it has a very positive click that allows you to still feel in control more than you might think with them that close together. The Kahles 6-24×56 seems to be a great balance of a lot of adjustment with a wider, shorter turret design. But honestly, like most things dealing with ergonomics, this is another one of those things that comes down to personal preference. I’m just trying to provide what data I can to help you make an informed decision, and pick the rifle scope that best fits your taste.

In Part 2 of the ergonomics results, I go through each scope and point out the unique features of each, include videos that demonstrate the scope from the shooter’s perspective, and also include a full photo gallery for each scope with shots of every angle.

Other Post in this Series

This is just one of a whole series of posts related to this high-end tactical scope field test. Here are links to the others:

- Field Test Overview & Rifle Scope Line-Up Overview of how I came up with the tests, what scopes were included, and where each scope came from.

- Optical Performance Results

- Summary & Part 1: Provides summary and overall score for optical performance. Explain optical clarity was measured (i.e. image quality), and provides detailed results for those tests.

- Part 2: Covers detailed results for measured field of view, max magnification, and zoom ratio.

- Ergonomics & Experience Behind the Scope

- Part 1: Side-by-side comparisons on topics like weight, size, eye relief, and how easy turrets are to use and read

- Part 2 & Part 3: Goes through each scope highlighting the unique features, provides a demo video from the shooter’s perspective, and includes a photo gallery with shots from every angle.

- Summary: Provides overall scores related to ergonomics and explains what those are based on.

- Advanced Features

- Reticles: See every tactical reticle offered on each scope.

- Misc Features: Covers features like illumination, focal plane, zero stop, locking turrets, MTC, mil-spec anodozing, one-piece tubes

- Warranty & Where They’re Made: Shows where each scope is made, and covers the details of the warranty terms and where the work is performed.

- Summary: Overall scores related to advanced features and how those were calculated.

- Mechanical Performance

- Summary & Overall Scores: Provides summary and overall score for entire field test.

PrecisionRifleBlog.com A DATA-DRIVEN Approach to Precision Rifles, Optics & Gear

PrecisionRifleBlog.com A DATA-DRIVEN Approach to Precision Rifles, Optics & Gear

Holy $#!@. This is amazing.

Thanks man! Glad you found it helpful.

Great stuff. Great job. Much thanks for a definitive report that is not available anywhere else. Keep ups the great work.

Sent from my iPad Ted Bristol

>

Starting to think those IOR’s are worth their salt even more so now. Just ready for the mechanical portion to seal the deal.

I’m looking forward to the reticle analysis in the “Advanced Features” section. I’m one of those who consider that a good reticle (like Horus or DT’s AMR) can make up for a lot ergonomics and/or mechanical problems by allowing you to not have to mess with the turrets at all after zeroing.

Absolutely. When I first heard people say mechanical precision wasn’t that important, I thought they were crazy. But if you use a hold-off reticle like the Horus … you’re exactly right. I read an article by Todd Hodnett in an issue of SNIPER magazine that came out a couple months ago. Hey really put this in perspective in a section of the article where he was explaining a lot of misconceptions people have with scopes:

Having said that, I still like to dial for elevation and hold for wind … but if you don’t have a scope that tracks or you have no way to test it yourself, you’d certainly be better off with a hold-off reticle. But I know some people who love hold-off reticles. I think it comes down to personal preference, and there isn’t a wrong answer here (unless you are dialing and haven’t made sure your scope tracks … that might be wrong).

I talked to Dennis Sammut, President of Horus, while I was planning all these tests, and he gave me some great advice for how to check mechanical precision. I actually used his Horus CATS targets in my tests, which are awesome. He said he designed the Horus reticle because he got tired of forgetting what revolution he was on, and missing shots because of that. He said maybe he gets distracted more easily than others, but it was too easy for him to get lost on what revolution he was on. I’ve made that mistake myself, and it is one of the most frustrating mental errors you can make. Dennis said there is no way to get lost on a Horus reticle, and he’s right. It’s a solid argument, and probably why so many people are moving in that direction. I even noticed a trend among pro shooters moving towards hold-off, Christmas tree style reticles. I covered that in a post a few months ago where I reviewed what scopes the top 50 shooters in the PRS were running. You can find that here: Best Rifle Scopes – What The Pros Use.

Thanks for the comments!

@Cal: Thank you for the great, detailed reply. I did pore over your “Best Rifle Scopes – What The Pros Use” article multiple times already. Actually, that’s where I found out about the AMR the first time. Right now, I like the AMR better than the H58/H59, but I am curious how the Kahles 6-24×56, which is the only one I know using the AMR fares, in the other respects, against the scopes that have various Horus reticle versions.

Great job Cal. I have never seen anything like this before.

This really is a great test and one that I think people will use for comparison for years to come. It would be great if you would do separate “value priced” and “mid-range” comparison tests in the future so that you have the entire package.

Thanks, Brent. I had originally planned to also do this for scopes in the $500-1500 price range in the fall. But honestly, this turned out to be A LOT more work than I originally anticipated. So I might need a little longer to recover, especially since I just do this in my free time. It’s eaten up most of my free time for the past 3-4 months!

But I bet the pain will fade over time and my guess is I’ll end up doing another one. I originally intended to develop a 100% repeatable set of tests that might could evolve into a set of benchmark tests. That would allow me to test scopes later and the results be comparable to previous tests. That means the set of data would just grow over time. Again, I’m not sure I’ll pursue this, but at least I was able to get this info in your hands. I’m glad you found it helpful. I’m hopeful it will start a new trend of a data-driven approach in our industry.

Cal, I can definitely appreciate the amount of time and the thorough process that you setup for these tests. I’m a mechanical engineer and see this sort of thing all the time but to do this with your free time is something else! A repeatable set of tests to truly compare a $6,000 scope to a $500 scope is something that is really lacking in the world (purely subjective at this point) and I think most people would really use such a tool.

Amazing attention to detail. Well thought out and executed, and a plethora of great information! Thank you!

Cal, I really can’t add anything new to what has been said above. Simply outstanding work and thank you!

Thanks, Fred. I really tried to offer some new insight in this area specifically. This is a crucial aspect to consider when you’re dropping this much on a scope, yet prior to this post … there was virtually nothing written on it, or at least no good objective, side-by-side comparison with this level of detail (that I’d ever seen). Glad you found it helpful! That’s why I do this.

Thanks,

Cal